This is prompted by a question that arose during a meeting for ArtUK’s project to pilot the automatic updating of data on their website by speaking directly to the databases of contributing organisations – but it’s not really about that, fascinating and welcome as the project is. At some point in the discussion the question of dates came up, and this reminded me of something that’s been bugging me for some time: have museums been recording their dates properly? It’s a matter I raised a couple of years ago in the users’ email list for the collections management system I use at the National Gallery, Gallery Systems’ TMS – where it was met with a resounding silence.

Let me explain. Most museum collections management systems allow users to record dates in two ways: as free text (sometimes called a ‘display date’), which could be as vague as ‘early fifteenth century’ or as specific as ‘2 February 1976’; and as a properly machine-readable date (or dates), following a standard format. The format that they use is almost always that mandated by ISO 8601, Data elements and interchange formats – Information interchange – Representation of dates and times.

Public domain.

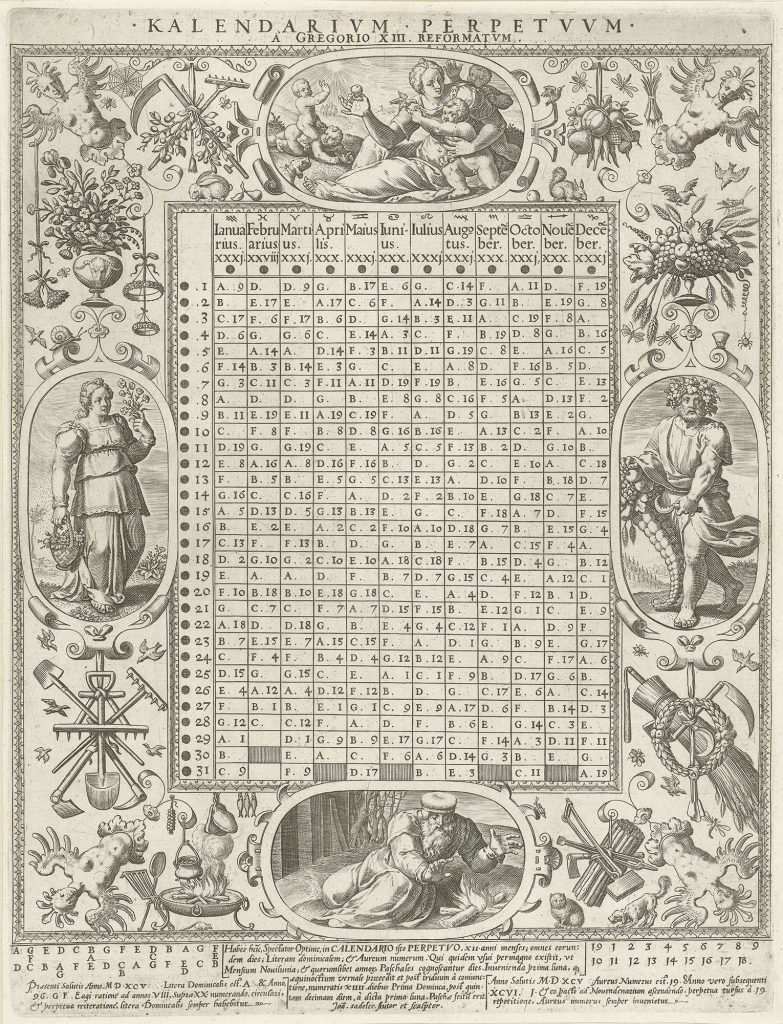

Public domain.The formatting element of ISO 8601 is quite simple; of the variants it offers, the one most often used in museum software is the basic YYYY-MM-DD (which can be reduced down to as little as YYYY for less precise dates). The problem is to do with calendars. ISO 8601 specifies that dates should be recorded using the Gregorian calendar – the calendar in use in much of the world today, first introduced in some countries on 15 October 1582 as a result of reforms instigated by Pope Gregory XIII, and designed to reduce the disjunction between astronomical time and calendar time that had crept into the previous Julian calendar because of the way that leap years were calculated: the Julian calendar was by then 10 days adrift of astronomical time. In other words, when the Gregorian calendar was first adopted, 4 October 1582 was, in some countries, immediately followed by 15 October 1582. (The days of the week, however, ran on in their normal sequence.) The calendar was adopted across the world gradually: it only came into use in the British Isles in 1752, when 2 September 1752 was followed by Thursday 14 September 1752 (after me, now: ‘Give us our eleven days!’)

But what about dates before 15 October 1582? According to ISO 8601, these can only be recorded ‘by mutual agreement of the partners exchanging information’; they should be recorded using the proleptic Gregorian calendar, which simply extends the Gregorian calendar back in time before its creation. This means that the precise dates of events that took place in the past should be shifted accordingly when entered into museum databases, if they are actually to adhere to the standard they profess to use. For example, Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne arrived at its destination, Ferrara, on the Julian calendar date of 20 January 1523 (or thereabouts) – or 30 January in the proleptic Gregorian calendar.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.I’d like to ask anyone reading this who works in museum documentation: are you really recording pre-Gregorian dates in ISO 8601-formatted fields using the proleptic Gregorian calendar – or are you just using the Julian calendar, and formatting your dates to look like ISO ones?

I can understand why museums might not be implementing ISO 8601 properly. For one thing, it means that the proleptic Gregorian date needs to be calculated every time you enter a Julian date. For another, it leads to problems when we consider anniversaries. The Wikipedia article on the Gregorian calendar discusses the supposed coincidence of the deaths of both Cervantes and Shakespeare on 23 April 1616 – although, as Spain at that time used the Gregorian calendar, and England the Julian, Cervantes actually died ten days before Shakespeare, the interval by which the two calendars diverged in 1616. But in 2020, we will mark the anniversary of Shakespeare’s death on its calendar date, 23 April, and not 404 years (of 365/366 days) after it actually took place, on 3 May. In other words, our anniversaries are out of step with our calendars if the events being commemorated occurred under the Julian calendar. And museums, as memory institutions, do like to mark anniversaries – even more so when there are social media accounts to feed with regular content. To return to the example of the Titian painting I mentioned earlier: when should we tweet the anniversary of its arrival in Ferrara – on 20 January (Julian date) or 30 January (ISO 8601 date)?

But if we stick with Julian calendar dates entered using the ISO YYYY-MM-DD format, we’re setting ourselves up for further problems when we come to calendars where the new year doesn’t fall on 1 January. Many European states – including England and, before 1600, Scotland – marked the new year on Lady Day (the Feast of the Annunciation, 25 March). So in England, for example, 31 December 1602 was followed immediately by 1 January 1602, and 24 March 1602 by 25 March 1603. If we were to write these dates using the ISO format, and list them in chronological order, we would end up with the sequence:

- 1602-12-31

- 1602-01-01

- 1602-03-24

- 1603-03-25

Why does this matter? First of all, there’s the problem of putting chronological dates in order: YYYY-MM-DD dates should sort nicely, as they’re arranged in order from largest to smallest component. But they don’t, if the year doesn’t begin neatly at YYYY-01-01. Secondly, there’s ample scope for confusion: James VI of Scotland succeeded to the throne of England as James I, bringing about the Union of the Crowns, upon the death of his cousin Elizabeth I late on 24 March 1603 by the Scots calendar – but 24 March 1602 by the English. (To resolve the ambiguity, dates are sometimes written using the conventions ’24 March 1602/3′, or ’24 March 1602 Old Style (O.S.)’ / ’24 March 1603 New Style (N.S.)’.) In the United Kingdom, all this – the date of the new year and the divergence between the Julian and Gregorian calendars – was resolved by the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750.

And – if you’re not already banging your head on your desk in despair – ISO 8601 also creates a discrepancy with dates BC. The Julian calendar, as conventionally reckoned (remember, the Romans didn’t know to mark the birth of Christ in the year in which it occurred) included no year 0: 1 BC was followed immediately by AD 1. This is the convention followed in most historical texts. But the proleptic Gregorian calendar as used by ISO 8601 includes a year 0, with dates before that given negative numbers, and dates after (dates AD) given positive ones. So Julian 1 BC is in fact proleptic Gregorian 0, Julian 2 BC is proleptic Gregorian -1, etc.

So I can understand why museums might not actually be adhering to the standard that they profess to be using when they record dates. And with that happy thought I’ll sign off. For those of you who like to do things the old-fashioned way (and have some Italian), I find Adriano Cappelli, Cronologia, cronografia e calendario perpetuo: dal principio dell’era cristiana ai nostri giorni, 7th edn, Manuali Hoepli (Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1988, and reissued subsequently), ISBN 88-203-2502-0, a useful compendium of calendar-related information. My copy came with a calendar conversion program on 3.5″ floppy disk (remember them?), which I can’t get to run on Windows 10; fortunately, there’s now a superfluity of calendar converters online – John Walker’s, available here, has the added advantage of downloadable code that you can install locally should you wish.

Now, back to working out how to record fifteenth-century dates from Florence (using the Julian calendar and starting the New Year on Lady Day) in my collections management system.

Updates

- 17 February 2020: erroneous references to ISO 8901 corrected to ISO 8601 (thanks to @gndnet).

- 17 February 2020: erroneous reference to a 3¼″ floppy disk corrected to 3.5″ (thanks to Michael Comiskey).

- 18 February 2020: there’s a more extensive discussion of these issues in Miranda Lewis, Arno Bosse, Howard Hotson, Thomas Wallnig & Dirk van Miert, ‘II. Standards: Dimensions of Data. 3. Time’ in Howard Hotson & Thomas Wallnig (eds.), Reassembling the Republic of Letters in the Digital Age: Standards, Systems, Scholarship (Göttingen: Göttingen University Press, 2019) DOI:10.17875/gup2019-1146, pp. 97-117 (thanks to Arno Bosse).