Alongside the 200 online catalogue entries in 200 Paintings for 200 Years, and the bibliographies and exhibition histories I wrote about recently, the National Gallery has now put on its website a provenance for every painting in the main collection. This post talks in brief about why provenances are important, and what makes them difficult to deal with, before outlining what we’ve done at the Gallery.

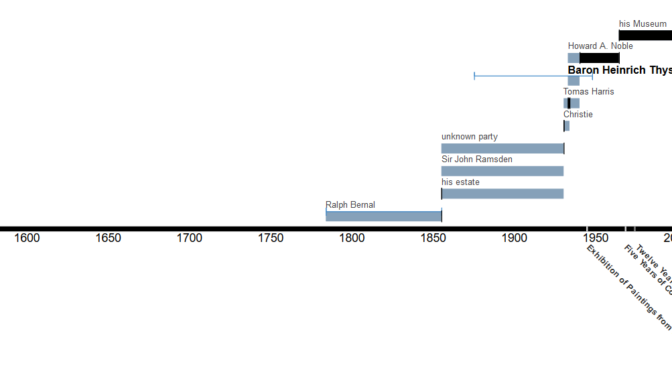

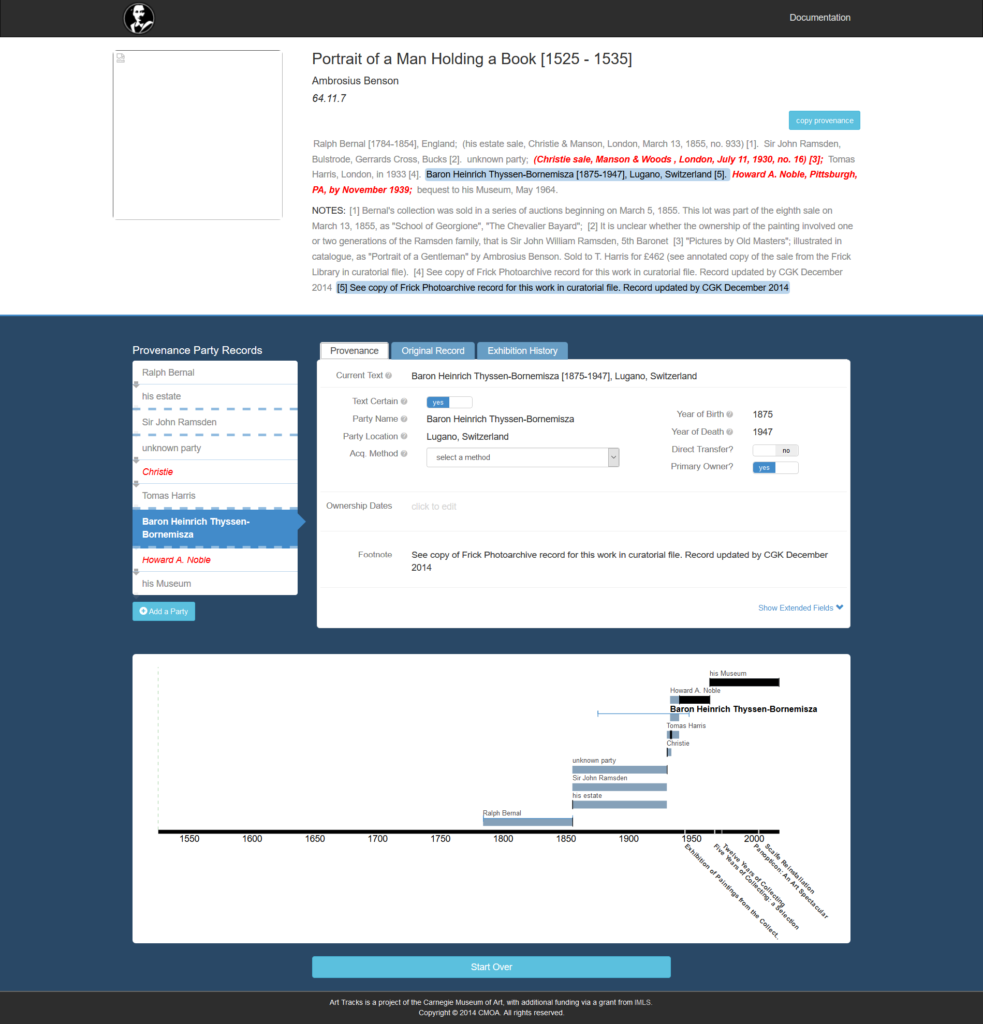

A note of caution: the image above is misleading. We haven’t published provenances as structured data, let alone visualisations. It’s taken from an old screengrab of Carnegie Museum of Art’s Elysa provenance-parsing tool, and I used it because it provides a visual representation of a provenance.

Why provenances are important

Provenance – the chain of ownership for a museum object from its creation to the present day – is vital information for many reasons: most importantly, it can help establish the authenticity of an object, and it identifies objects which were (or may have been) acquired or trafficked illegally or immorally at some point in the past. Different kinds of object have particular problems; for example, the Gallery, because of the nature of its collection, pays particular attention to the whereabouts of its paintings during the period of Nazi dominance in Europe, 1933-45.

This applies equally to loans: any reputable museum should be committed to not displaying any questionable object, whilst lenders may well request that their objects be granted immunity from seizure, which in turn requires the lender to demonstrate an unblemished provenance. Detailed checks of an object’s provenance are therefore a core part of the due diligence [PDF] that any museum should carry out before the object crosses its threshold; in the case of loans, publishing provenances online helps borrowing institutions with this process.

Why provenances are difficult

Provenances are often presented as free text: effectively, narrative descriptions of an object’s biography; but the ideal would always be for some kind of structured data, which makes it easier to reuse the information in different ways (for example, visualisations, or aggregations such as the virtual reassembly of a particular collection), and to retrieve information effectively. But provenance data is quite difficult to model: whilst it is basically a chain of events – changes in ownership – which take place at specific times and in specific places, involving particular actors and objects, the data is often uncertain: dates may be vague, actors may be only partially identifiable (if at all), it may not be clear whether the object involved in a particular event really is the one we are interested in. Add to this the way that a group of objects can be involved in one event, but only some of that group in others; that there’s a difference between physical possession and legal ownership; that one object may be owned by multiple people in proportions that change over time; and so on; and it’s easy to see why creating a structure for provenance data is non-trivial.

Which is not say that it hasn’t been attempted: for several years, a group of museums using the TMS collections management system (including the Gallery) have been meeting to try and draw up a set of specifications that could be used to incorporate structured provenance data within the system. Equally, emerging standards such as Linked Art now model provenances.

But how do we get from blocks of free text to accurate structured data? Ideally, provenance texts would be written in ways which make them easy to parse into structured data – all those complexities notwithstanding. But the standard mostly adopted by anglophone museums (if they use one at all), that proposed by the American Association of Museums (AAM),1 is very flexible. As part of the Art Tracks project, the Carnegie Museum of Art drew up a much more rigid version of the AAM standard, the CMOA Digital Provenance Standard, which was capable of being parsed into structured data using regular expressions using a tool called Elysa (‘named after Elysa Nicholl, Andrew Carnegie’s housekeeper’); but the standard remains stuck at version 0.2, published in 2016, and Elysa seems not to have got much further than a proof of concept.

That said, much of that work is now several years old, and developments in natural language processing and machine learning mean that those technologies may prove more fruitful as ways to extract structure from text – something being pursued by the Provenance Lab at Leuphana University, for example. But whatever is retrieved from the free text must be 100% accurate if it is to be useful – outputs cannot contain hallucinations.

Whichever way we choose to approach the problem, though, anything which means that provenance texts are written in a more predictable format will make them much more amenable to processing into structured data.

What we’ve done

The Gallery has a written provenance for all of its paintings. Mostly, these are contained in the published catalogue entry for the painting; uncatalogued works have their provenances given in the annual report that listed their acquisition. But these provenances have been written by many different people, and some of them date back many years (current catalogue entries go at least as far back as Martin Davies and Cecil Gould’s French School: Early 19th Century, Impressionists, Post-Impressionists etc. of 1970): they are phrased and laid out in many different ways, and can be extremely discursive; and they certainly pre-date the AAM and CMOA standards.

We have looked at standardising our provenances. An initial go at using the CMOA standard failed to attract the necessary buy-in; and so we have taken some time to draw up our own standard: less obviously structured than CMOA, but more so than AAM. Getting everybody on board has been crucial, but this has meant that, although we drew up and agreed our new standard, we did not have the time to reformat provenances for all 2,500+ objects owned by the Gallery before putting them on our redesigned website.

Instead, we have taken advantage of our interoperably-formatted catalogue entries (as described in my recent post) and used XSL templates to extract the ‘provenance’ sections from the printed catalogues wherever possible (or copy them from scans of the annual reports), and give them a quick tidy: we have removed footnotes, figure references and cross-references; copied the provenance form other paintings’ entries if necessary; corrected typos and applied formatting; and added metadata alongside the texts. Over 100 provenances have also been supplemented with information either drawn from other publications, or added directly by the relevant curator.

Like the bibliographies and exhibition histories, the provenances are stored in our TMS collections management system, from where they’re ingested into our CIIM middleware, which delivers data to our Umbraco web content management system. To find them, on a painting’s web page, scroll down to below the image and, in the ‘Key facts’ area, click on ‘Provenance’ – see, for example, Titian’s Death of Actaeon (NG6420).

We have not abandoned our plans to convert provenances into structured data, but we do need to review the best way to do this – at the moment, an initial manual tidy of the texts followed by the application of natural language processing / machine learning seem likely.

Acknowledgements

As with our work on the catalogue entries, bibliographies and exhibition histories, putting these provenances online has been the culmination of work by many people, stretching back for years.

Our new provenance format was drawn up by Carlo Corsato, with much help and advice from Susanna Avery-Quash. Data from the various catalogues was extracted using templates developed by Kate Byrne, and Jeremy Ottevanger of Sesamoid Consulting, whilst the digitisation of the various Annual Reviews was overseen by Katie Holyoak.

The resulting data was reviewed and tidied by Tania Adams and Gianna Scavo, assisted by Hugo Brown; updates and advice were provided by Anna McGee, Annabel Bai Jackson, Bart Cornelis, Carlo Corsato, Carol Plazzotta, Chiara Di Stefano, Chris Riopelle, Christine Seidel, Claire Hallinan, Daniel Ralston, Emma Capron, Imogen Tedbury, Isobel Muir, Laura Llewellyn, Maria Alambritis, Mary McMahon, Nicholas Flory, Nina Cahill, Sarah Herring and Tom Henry.

The CIIM was configured to accept the new data by James Huish at Knowledge Integration, in liaison with Jude Dicken at the Gallery. The entries have been incorporated into our new website collections pages: the initial interface designs were made by Numiko, in collaboration with the Gallery’s internal UX/UI team. Over the last year, Caroline Kha and Antonio Sauro worked with Lucinda Blaser, Nejra Hadzimejlic and Jim Gettrup to iterate the designs for integration; Nejra and Jim also built and implemented the final designs and the data integration.

- Nancy H. Yeide, Konstantin Akinsha, and Amy L. Walsh, The AAM Guide to Provenance Research (Washington DC: American Association of Museums, 2001), pp. 33-4 [↩]