A couple of years ago, I wrote a piece for this site about a series of objects from Antarctica that had been collected by the Horniman Museum and – in several cases – subsequently disposed of. I also wrote a longer essay for the Horniman’s website about the objects. In the latter piece, I noted that we had been unable to find some of the better-documented objects: several birds’ eggs donated by a person named in the registers as C. T. Colbeck (see also here). I was, therefore, delighted to receive a tweet a couple of weeks ago from my former colleague Justine Aw, saying that the eggs had been found whilst working through the Horniman’s collections following a collection review.

https://twitter.com/NotCritters/status/742762671515303936

The eggs were turned up by Justine, who works as a Collections Assistant at the Horniman; Jo Hatton, the Keeper of Natural History; and May Webber, a volunteer at the Museum, as they were working through the collection of birds’ eggs whilst following up the results of the Museum’s Bioblitz collection review.

According to the register of the Horniman’s natural history collections the eggs had been presented by C. T. Colbeck, the son of the eggs’ collector, Captain William Colbeck. As a result of my first article, Captain Colbeck’s granddaughter, Sandra Margolies, contacted me, and she has kindly provided some more information about ‘C. T. Colbeck’, her father. His initials as recorded in the register are in fact mistaken (an understandable error which I repeated when reading the letter from which they were taken, which Justine found alongside the eggs): his forenames were Clements Markham, though he was known as Mark.

Mark Colbeck owed these distinctive names to Sir Clements Markham, a president of the Royal Geographical Society and one of the prime movers behind British Antarctic exploration during the ‘Heroic Age’ at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This is not surprising when we remember that Mark Colbeck’s father, William Colbeck, was a member of the British Antarctic Expedition (the Southern Cross expedition) of 1898-1900, the first to overwinter on the Antarctic mainland, and briefly held the record for Farthest South; and the commander of the Discovery Relief Expedition, sent by Markham to resupply Captain Scott’s first Antarctic expedition in 1902.

I’m delighted to be able to say that Captain Colbeck is a less neglected figure than I at first thought: Sandra Margolies pointed out that he has his own entry in the Dictionary of National Biography [free access possible with most UK local library cards], which I had failed to find; and she has now published her own account of his life: Sandra Margolies, ‘Captain William Colbeck: from Hull to Catford via Antarctica’, Lewisham History Journal, 22 (2014), pp. 32-57.

The Horniman’s natural history register lists Mark Colbeck’s gift thus:

[NH.38.]2 / January 29 [1938] / Eggs (4) of Pygoscelis adeliæ / South Victoria Land / Obtained by Capt. Colbeck, National Antarctic Relief Expedition 1902 / Presented / Mr. C. T. Colbeck

[NH.38.]3 / 〃 / Egg of Megalestris maccormicki / 〃 / 〃 / 〃 / 〃

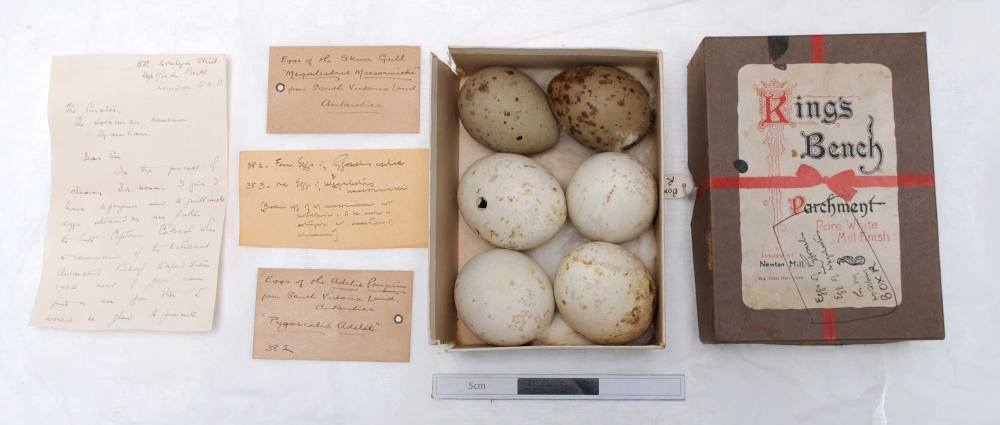

But how do we know these are the eggs found a few weeks ago? Luckily, they fulfilled the dreams of all of us who work in museum documentation by being accompanied by clear written evidence in the form of two labels, an additional note, and a letter from the donor. The first label is clear enough:

Eggs of the Adelie Penguin / from South Victoria Land. / Antarctica / “Pygoscelis Adelie” / 38·2

It both names the species, and gives the museum number that identifies these Adélie Penguin eggs as the ones presented by Mark Colbeck. The second label is equally clear, although it lacks the museum number:

Eggs of the Skua Gull / “Megalestris Maccormicki” / from South Victoria Land. / Antarctica

The note also identifies the eggs as:

38·2 – Four Eggs of Pygoscelis adeliæ / & / 38·3 – One Egg of Megalestris maccormicki

In the letter, Mark Colbeck (whose Ms are easily mistaken for Ts) writes from 58 Evelyn Street, Deptford Park, London SE8 to offer the eggs to the Horniman. Interestingly, he describes two eggs from each species, and refers to the skua eggs as guillemots’ – the assumption must be that he mistook the species. He says that they were collected by his father Captain (i.e. William) Colbeck during the National Antarctic Relief Expedition of 1902 (the Discovery Relief Expedition). As I said in my piece on the Horniman’s website,

if the eggs really were collected in ‘South Victoria Land’ during that expedition, then they must have come from Cape Adare, where Colbeck had previously over-wintered … he does not seem to have landed anywhere else in Victoria Land during the relief expedition.

The quantity of eggs is a problem. Mark Colbeck mentioned two penguin and two skua eggs. The register lists the four penguin eggs that Justine found, and I think we must assume that when he came to deliver the eggs to the Horniman, Mark Colbeck brought in two extra penguin eggs. But how to explain the fact that, although his letter mentions two skua eggs, and there are clearly two in the box found by Justine, the register only mentions one? All is made clear by an addendum at the bottom of the note, which says:

[Broken egg of M. maccormicki not / catalogued: to be used or / destroyed at discretion of / Museum]

This leaves the Horniman with an interesting question: should they put the broken egg through the process of formally accessioning it into the collections, which would involve drawing up a written proposal, reviewing it at a meeting of the committee responsible for acquisitions, and obtaining the Director’s approval for the acquisition; or should they leave it without the protection afforded by being a member of the ‘permanent’ collection, and make use of it in some other way?

All this paperwork means that, of the Horniman’s Antarctic relics, Captain Colbeck’s eggs are amongst the most thoroughly documented. Sadly, Mark Colbeck’s letter says nothing about the other Antarctic objects given to the Horniman and associated with his father. These are listed in the very cursory accession register for anthropological objects as:

Mr Colbeck, 67 Queenswood Road Forest Hill. / Collection of his father’s Antarctic relics (S.S. Relief Ship “Morning”)

Sandra Margolies tells me that in 1938, William Colbeck’s widowed sister-in-law Annie Maud was living at 67 Queenswood Road; her husband, Haggitt Colbeck, had been William’s brother. Of William’s four sons, William Robinson Colbeck (‘Bill’, who sailed with Sir Douglas Mawson as second officer and navigator in Scott’s old ship, the Discovery, on the British Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE) voyages from 1929 to 1931) and Mark Colbeck were both married and had households of their own, whilst Haggitt Garth Mulock Colbeck had emigrated to Canada earlier in the decade. This leaves only John Christopher Colbeck, known as Chris, as likely to be staying with his aunt Annie at Queenswood Road, and so it seems reasonable to assume that he gave the Horniman the additional Colbeck Antarctic material. This raises the possibility of an even more systematic campaign than I had first thought by the Horniman’s curator at the time, L. W. G. Malcolm, to acquire a set of ‘Antarctic relics’ for the Museum: after all, the entry in the anthropology register comes immediately before one recording the donation of objects related to Sir Ernest Shackleton.

It seems from later documentation at the Horniman that these additional objects associated with William Colbeck included a series of photographs associated with the Discovery expedition, presumably the ten prints and six negatives listed by the Scott Polar Research Institute under numbers P62/44/1-10 and P62/45/1-6 respectively, as presented by Captain Colbeck; and perhaps a pair of skis.

The discovery of Captain Colbeck’s eggs means that now only three of the Horniman’s former collection of relics from the ‘Heroic Age’ of Antarctic exploration remain to be tracked down: the lifebuoy from Shackleton’s last ship, the Quest, which seems to have vanished without a trace; a wire circlet from Shackleton’s famous open boat, the James Caird, in which he sailed 800 miles across the Southern Ocean; and a pair of skis – and I have an idea about those.

Updates

- 30 June 2016 : clarified the circumstances of the eggs’ discovery after receiving information from Jo Hatton, and proposed Chris Colbeck as the donor of the other relics as a result of information from Sandra Margolies.

- 14 July 2016: changed the occupants of 67 Queenswood Road from Gladys and Joe Ward to Annie Maud Colbeck, following receipt of further information from Sandra Margolies.

It is not directly related but my father RAAF Group Captain Eric Douglas (1902-1970) was with William Colbeck on BANZARE. He and William got on really well. Eric was one of the two RAAF pilots.

Dear Sally, I have copied this comment to my cousin Carolyn Irvine, who is the younger daughter of William Robinson Colbeck. If you would like to get in touch with her, contact me and I’ll forward any message.

Sandra Margolies

Not sure if a reply went – that would be nice

Hello, Sally, I’ve just been researching and writing about your father so it’s good to know that he and Colbeck Jnr got on well. He and Hurley also seem to have got on well too, and I’m sure Hurley had tales to tell about his adventures!

Sally, thanks – I’m sure the Colbeck family will be pleased to hear about this!

Hello Sandra, I read this article with some interest, as I am one of Markham’s step-grandsons (following his 2nd marriage, to Margaret Maw). My family and I spent most Easters with Markham and Margaret in Wales as we grew up. Would love to touch base and learn more from your side of the family!

Andy, thanks – this page seems to be becoming a clearing house for Colbeck family connections!