The text of a webinar organised by Collections Trust, 13 October 2022

I’m talking today about the Exhibition Object Data Exchange Model, EODEM, which is a project organised by CIDOC Documentation Standards Working Group (the DSWG). But I’d also like to thank Collections Trust for organising the webinar today, and Sarah in particular for facilitating it.

Our aim is very simple: to make it possible to export object exhibition data from a lender’s collections management system at the touch of a button, and import that data into a borrower’s system – produced by a different software vendor – just as easily. The process should work like this:

- We start with an object

- Which is recorded in a database

- The lender opens their Collections Management System (CMS) and finds the object’s record

- They press an EODEM export button

- And an EODEM file is created

- The lender emails EODEM file to the borrower

- The borrower receives the email and saves the file

- They open their CMS

- And press an EODEM import button

- And the object’s data is stored in the borrower’s database

Why are we working on this?

We all know that we – or our colleagues – spend huge amount of time copying and pasting – or, worse, retyping – object information between collections management systems and forms or emails.

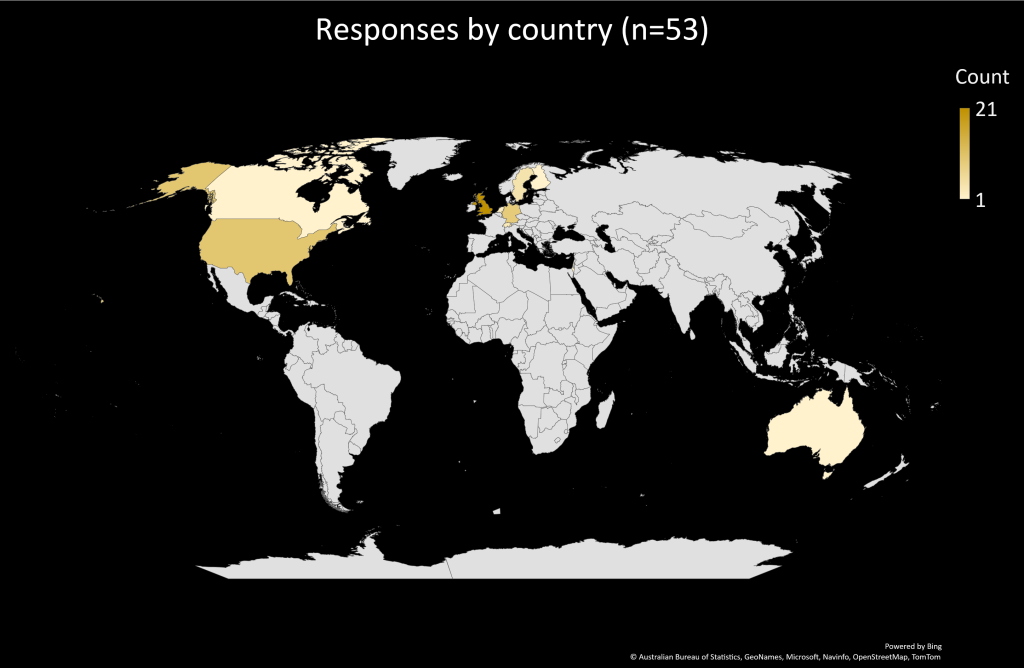

But we don’t know how much time, so we’ve been running a survey over the summer and autumn of 2022 to find out. Today, I’ll present our preliminary findings. First of all I should speak about our sample. We had 53 usable results (although not everyone filled in all the questions). Because of the channels used to circulate the survey, there’s a strong geographical bias to the sample:

| Australia | 1 |

| Canada | 1 |

| Finland | 1 |

| Germany | 8 |

| Israel | 1 |

| Netherlands | 2 |

| Sweden | 4 |

| Switzerland | 3 |

| United Kingdom | 21 |

| United States | 10 |

- 40% of responses came from the UK

- Around 18% each came from Germany and the United States

- The remainder were distributed between a further 7 countries

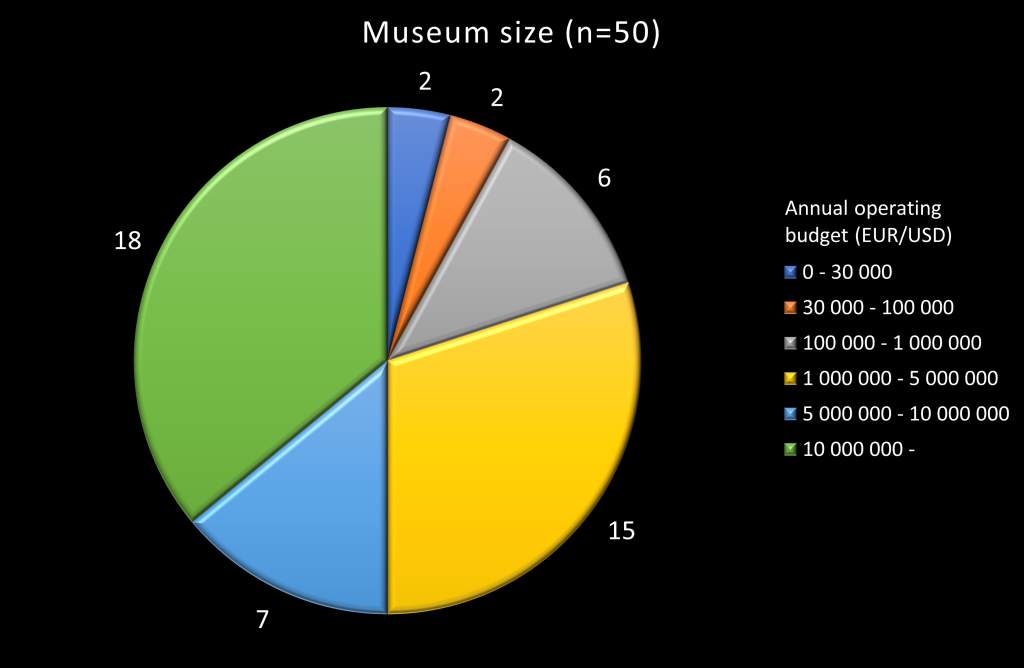

As we might expect, a third of our responses came from the largest museums – indicated by an annual operating budget of more than 10 million Euros or US dollars, and half were from museums with a budget of 5 million or more. Only 20% of responses came from museums with budgets less than 1 million Euros or dollars.

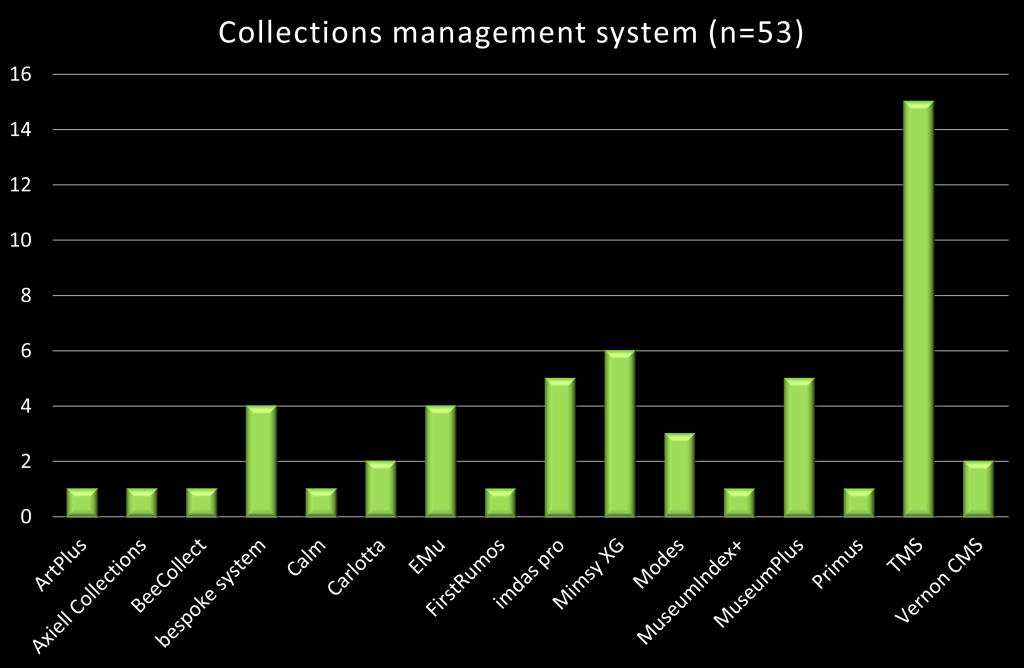

Again, due to the channels available to me, there’s a strong bias towards TMS users in the sample: they make up nearly 30%. Next are Mimsy XG users, closely followed by users of imdas pro and MuseumPlus, then by users of EMu and bespoke systems. (It’s worth noting that if we lump all Axiell users together they account for 23% of responses.)

Now on to the meat of the survey: how many objects do museums lend or borrow every year?

| Loans out | |

| minimum | 2 |

| median | 47 |

| mean | 149 |

| maximum | 3000 |

| Loans in | |

| minimum | 0 |

| median | 85 |

| mean | 200 |

| maximum | 1000 |

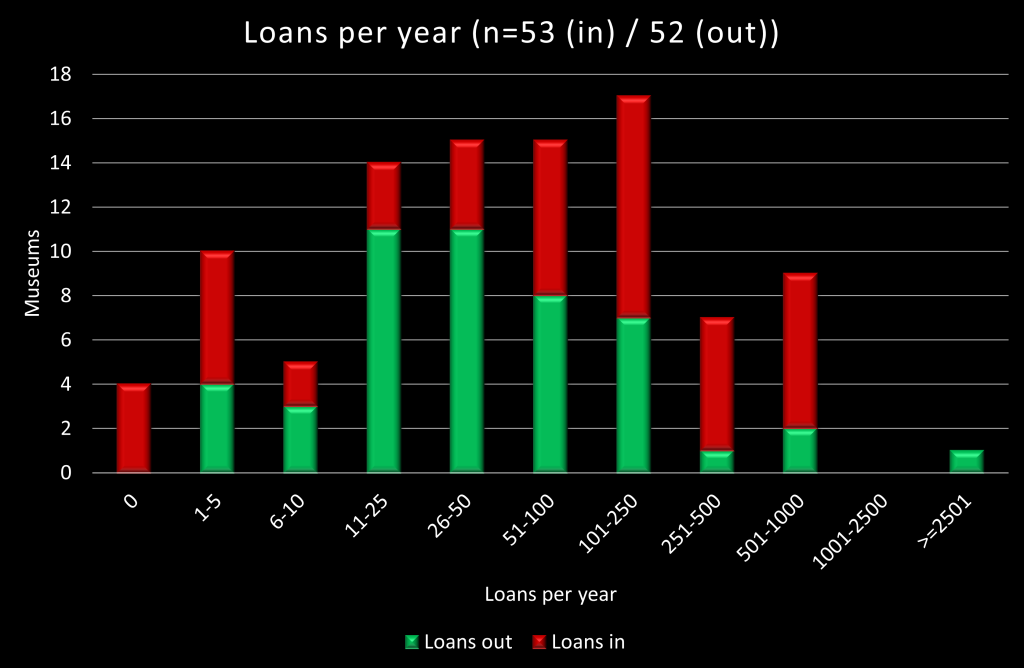

On the chart, I’ve grouped the number of objects lent per year into bands – it’s important to note that the scale along the horizontal axis is not linear. The bars show the number of museums which fall into each band: green for loans out, red for loans in. Museums with small volumes of loans tend to lend more objects than they borrow; but those with higher volumes of loans tend to borrow more than they lend. Generally, for both loans out and in, the majority of museums lend or borrow fewer objects, whilst a few museums lend or borrow significantly more – so the medians for both types of loan are significantly less than the means: a medium of 47 objects lent and 85 borrowed, compared to a mean of 149 lent and 200 borrowed. But do bear in mind the maximums: 3,000 objects lent and 1,000 borrowed.

| Loans out | |

| minimum | 0 |

| median | 15 |

| mean | 26 |

| maximum | 180 |

| Loans in | |

| minimum | 0 |

| median | 17.5 |

| mean | 29 |

| maximum | 240 |

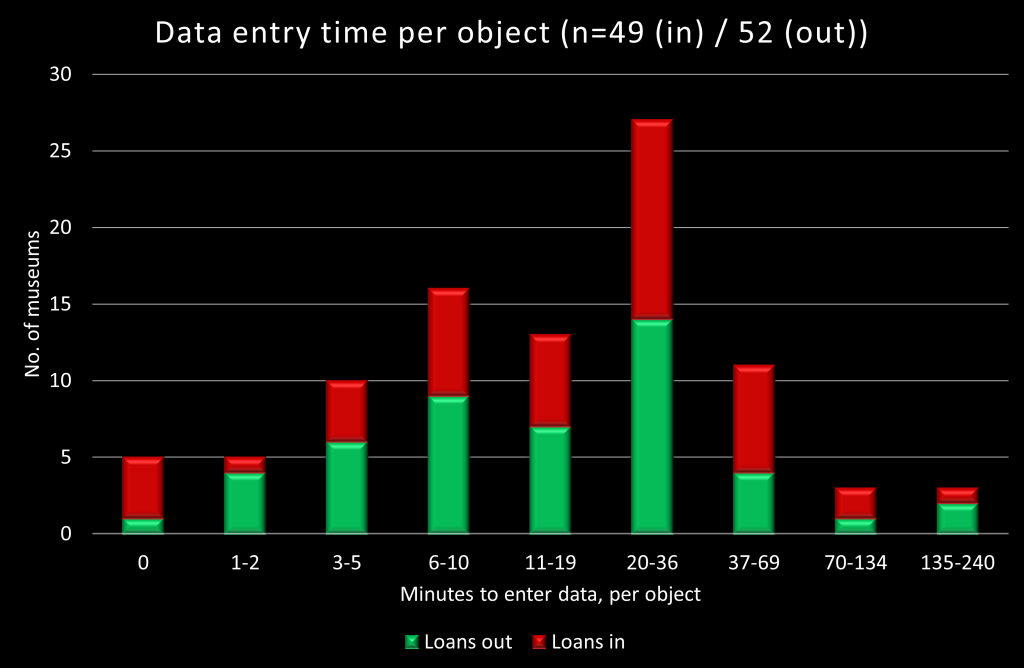

But when it comes to the time spent on data-entry, the differences are significantly reduced, with medians of 15 and 17½ minutes per object for loans out and in, compared to means of 26 and 29 minutes for loans out and in We shouldn’t be surprised to find that loans out generally take a little less time, as lenders can often export the data from their collections management system directly into reports. We do have two quite worrying maximums, of 3 hours per object for loans out, and 4 hours per object for loans in. But in short, the burden generally falls slightly more heavily on the borrowing institution.

| Loans out | |

| minimum | 0.00 |

| median | 8.75 |

| mean | 26.87 |

| maximum | 375.00 |

| Loans in | |

| minimum | 0.00 |

| median | 33.33 |

| mean | 88.85 |

| maximum | 525.00 |

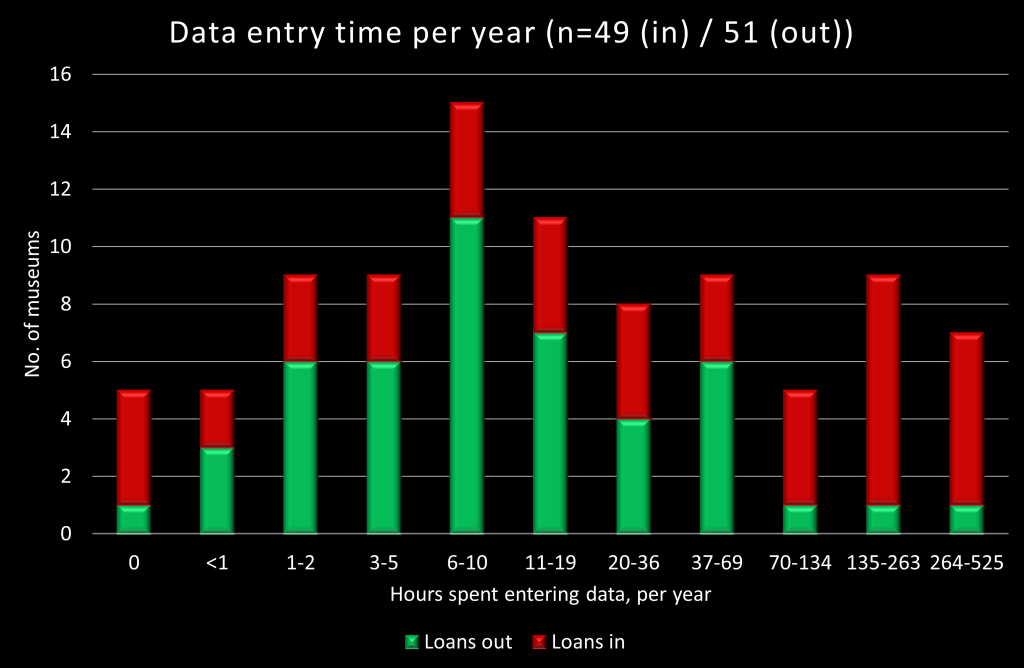

When we look at the time spent per year on loan–related data-entry, shown here in hours, then that difference become quite obvious: the median for loans out is 8¾ hours per year, for loans in it is 33⅓ hours. Once again, a few institutions report much longer times, which gives us means of nearly 27 hours per year for loans out, and nearly 89 hours for loans in; and maximums of 375 hours for loans out and 525 for loans in.

Let’s focus on those figures for loans in, and convert them into days spent on data entry over a 10-year period. We’ll assume that staff spend a full 7 hours a day on data-entry. This gives a median time spent on data entry for loans over a ten year period of 48 days, a mean of 127 days – very nearly 7 months, so well over half a working year. And in the case of one institution, 750 days: nearly 3½ working years. I won’t try and convert these figures into salary costs – there are too many variables – but it’s clear that there’s a significant potential to make long-term savings if we can automate loan-related data entry.

How are we doing this?

The EODEM project evolved during a series of CIDOC conferences. It began with a discussion between Rupert Shepherd, Jonathan Whitson Cloud, and Norbert Kanter of Zetcom at the CIDOC awayday, during the 2016 ICOM Triennial at Milan. In Tbilisi in 2017, the CIDOC Documentation Standards Working Group held a workshop with documentalists, to identify the units of information that would be needed for an exchange of exhibition data. The following year, 2018, in Heraklion, at a round table discussion with various software vendors, we agreed that the project was doable, and produced the first draft of the EODEM data profile. The project stalled in 2019, and then, as we reconvened in early 2020, Covid hit; so we have been working as a small group meeting online, Including online presentations at both the 2020 and ‘2021’ CIDOC Conferences, where we held workshops for system developers, discussing some of the potential problems or questions that might arise during the development process.

Our regular meetings include representatives from the DSWG and several software vendors (some of whom are just discussing the standard – not all the vendors are implementing it just yet). Other developers receive notes from meetings.

Over the last two years, we’ve been focussing on the creation of a final data profile, comprising:

- A final list of units of information;

- An agreed data standard with which to encode the data and a file format in which to transfer it; and

- Documentation to support the integration of the standard with software systems.

We’ve already identified several problems which, as a real-world system, EODEM needs to address.

For our data standard, we have settled upon CIDOC’s standard for Lightweight Information Describing Objects (LIDO). We are using the new version, 1.1, released in December 2021; in fact, EODEM’s needs have informed some of the changes introduced in the new version. This means that, if a collections management system can already export or import LIDO data, it’s already very close to being able to handle EODEM data, too.

This decision also chose our file format for us: LIDO uses the long-established and highly-flexible eXtensible Markup Language, XML.

After much discussion, we’ve settled upon a set of units of information which we feel are useful, without being too extensive. There are currently 109 of them; and this is where I add, in large, friendly, letters, the words ‘Don’t panic!’1

Let’s look at those units of information in more detail. First of all, 33 of them are ‘wrapper’ units which contain no actual data, but only descendant units. 14 units are made up of keyword / identifier pairs; and for six of those pairs, we only require the keyword element (if it is included) in the record. Another one unit is effectively duplicated because of the way we are implementing LIDO – which leaves us with 69 units of information. Even at this point, I doubt any collections management system has fields for every one of these; never mind a museum having data in all of these fields. Again, though, I’ll say, ‘don’t panic’ – because, of these units of information, only 13 are mandatory.

If we focus on those mandatory fields, it’s important to know that we expect that seven of them will be filled in either with system values, or standard values that are applied to every record upon export. The key point is that EODEM works on the principle that anything is better than nothing, and so the only mandatory units of information for an EODEM record where we expect values to be held as dynamic data with the collections managements system are:

- Object Type

- Title or Name

- Title Type (which in many systems may also be a default value filled in on export)

- Title Language (again, quite possibly a default value)

- Object Identifier

- And the type of record – whether it represents a single object or a group – which is mapped to a specific set of Identifier / Keyword pairs on export

If a system can export or import these seven fields, then it is EODEM compliant. And if a museum can provide four pieces of information –

- Object Type

- Title or Name

- Object ID

- Record Type

– then it can provide an EODEM record. Obviously , we hope that museums are able to provide more data, and that collections management systems will be able to export or import into more fields – but this is all that’s required for an EODEM record.

Where are we now?

We’ve spent the last months establishing EODEM as a formal profile of LIDO; Richard Light has very kindly been doing the bulk of the work. EODEM will be the first formal LIDO profile to be implemented within an integrated technical framework, which takes the form of:

- A single XML document, which contains:

- A description of EODEM in the form of changes to the LIDO XML Schema

- Human-readable documentation of the EODEM profile

- This single document can then be used to generate:

- An XSD schema file to validate EODEM LIDO records

- Human-readable documentation in HTML,

- and in PDF, comprising a list of units of information and how to extract them from the EODEM document, helping developers query documents for import

- An HTML outline of an EODEM document’s structure, helping developers construct documents for export

- We also have a sample EODEM document with real-world examples,

- And we have an XSLT file embodying a set of Schematron rules to provide richer validation (and more useful failure messages)

We think that these are far enough developed, and sufficiently mature, for us to have launched the current release of the EODEM profile, version 0.08, as a public beta at the CIDOC conference in Tallinn in May 2022.

Software developers now have access to the resources I’ve just described, as well an online viewer to preview EODEM records. We can also demonstrate proof of concept importers and exporters for an EODEM record in MuseumPlus and Modes. (And here, I’d like to say a particular thank you to Jette Klein-Berning at Zetcom, and Richard Light, formerly of the Modes Users Association, who have been doing the bulk of the heavy lifting when it comes to XML processing.) We still need to finalise sample tools and templates to show developers how to work with the raw XML file, but these are very nearly complete.

It’s also becoming clear to us that EODEM has the potential to be useful in other areas of museum and museum-related work, beyond exhibition organisation:

- The information in an EODEM record is just what’s needed by design companies when designing and fitting-out new displays, and by the makers of display cases

- Aspects of the information are needed by shipping and insurance companies when planning the transport of museum objects

- EODEM could also provide a mechanism for sharing object data when managing a shared store, if the museums using it have different collections management systems

And – with some changes to cover additional types of object description – EODEM might also be used to deliver data for apps and audio guides, although this would be a future development of the model.

What’s next?

The next stage is to test the beta profile by actually trying to develop importers and exporters. We hope that as many system vendors as possible will do this, and tell us how they get on. So far, we already have nine software suppliers on board.

| Company | Product | Exporter | Importer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axiell | Axiell Collections, Mimsy XG | under development | under development |

| Axiell / Musoft | Museion | under development | possibly |

| Gallery Systems | TMS | planned | under development |

| Knowledge Integration | CIIM | planned | no |

| KulturIT | Primus, DigitaltMuseum | under development | under development |

| Modes Users Association | Modes | under development | under development |

| Sistemas do Futuro | in arte, in patrimonium | planned | no |

| Userix Oy | Collecte | planned | possibly |

| Zetcom | MuseumPlus | under development | under development |

All nine are already either developing, or planning to develop, an EODEM exporter – and four are working on an importer, too. Once we have reviewed and incorporated developers’ initial feedback, we will be ready for a stable release of EODEM Version 1, which we hope to be able to announce this winter.

So, what resources are available to help you work with EODEM? You can find links to all necessary files at the project’s home page on the CIDOC website; this also includes:

- A list of Frequently Asked Questions

- Links to previous presentations on EODEM

- A list of software suppliers who are currently implementing EODEM

And we have an online viewer which will allow you to preview EODEM files.

If you want to get really involved, you could join our monthly meetings – just let me know via my website. But the key step you can take, if you think EODEM is a worthwhile initiative, is to ask your collections management system supplier to incorporate it into their system.

And why should you, as a documentalist, start asking your supplier to introduce EODEM?

- It will save you and your colleagues time, which you can use for more rewarding tasks than copying and pasting data

- It will improve data quality – there’ll be fewer typos or copy / paste errors, and the system will automatically put data into the correct database fields

- It will help you show your colleagues how the collections management system (and international standards!) can help them do their work

And did I mention that it’ll save you time?

If you go to the EODEM website, you’ll also find a link to the survey. Our sample is still small and un-representative, so please do go away and fill it in if you haven’t done so already (if you have: thank you!) – and ask all your contacts to do the same. We hope to report revised findings at the European Registrars Conference in Strasbourg in November.

Notes

- For a full list as of the time of writing, see the EODEM 0.08 specification at https://cidoc-data.org/shared-files/3300/EODEM_profile_definition_0_08-1.pdf. [

]