A lightning talk, written with Joe Padfield and Rob Tice, presented at Museums+Tech 2019: Openness, held at the British Library, London, on 18 October 2019.

Abstract

How can information be opened up within an organisation? The National Gallery was faced with a series of different systems, all holding data related to the collection – but speaking to each other only intermittently. This issue was solved with the installation of a middleware system to combine and deliver data from these eight different data sources as a seamless whole.

Our paper will look at the implications this has had for how we work with our data, and as an organisation. We will also touch upon the benefits of opening information up within our organisation, and some projects that are currently using – or are planning to use – our data, which will be delivered using established, open standards.

Text

The National Gallery is unusual as a museum: it has very few actual objects (2,381 in our main collection); but these works are incredibly well-documented.

The Gallery has probably more knowledge about its own collection than any other museum in the world. That’s knowledge that we want to share, it’s knowledge that we want to put out on the internet.

Gabriele Finaldi, Newsnight, BBC2, 4 January 2016

We once led the way in publishing digital collections information, and we still want to open up as much of our knowledge as possible, and share it. But we couldn’t do that easily even within the Gallery.

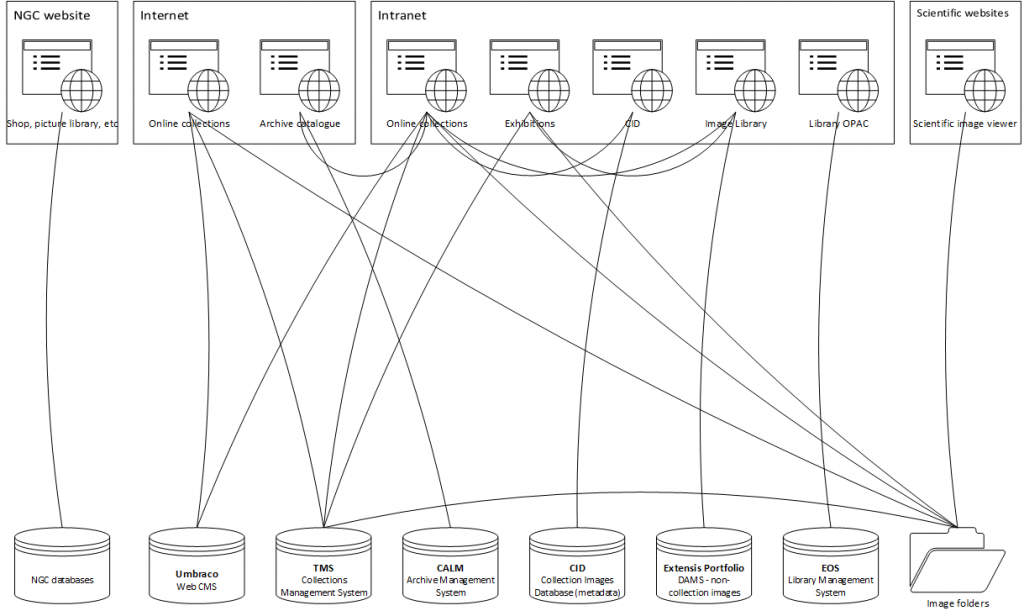

Looking only at our existing structured digital resources relating to our collections, they are stored in eight different systems, used for managing collections, libraries, archives, images, narrative texts and room bookings.1 An update in one system – say to an identifier – has to be made by hand in the other systems. It’s unsustainable to make individual connections to each data source for every system that uses collection data. So first we needed to aggregate our data and present it all as a single, sustainable source.

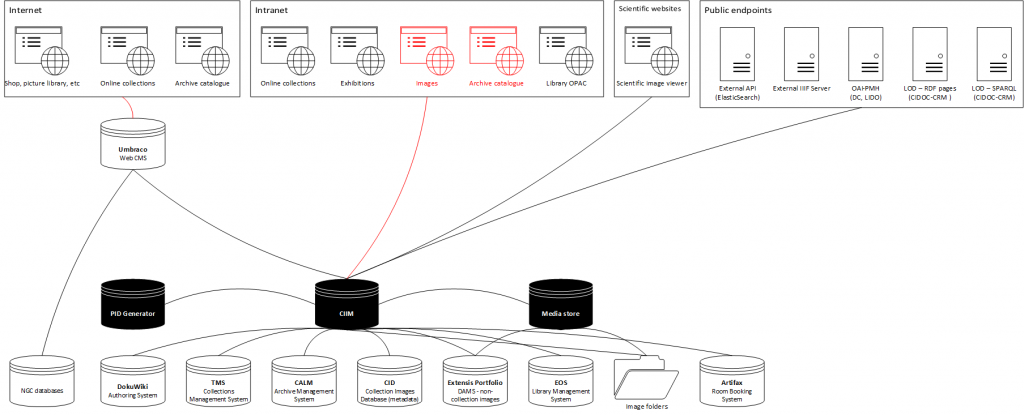

We went to tender and selected Knowledge Integration‘s Collections Information Integration Middleware, the CIIM. This is a stack of open source systems, which: aggregates data from multiple sources; enables users to review and if necessary augment the data; and publishes it via a series of standards-compliant endpoints. It has interfaces to manage the data and the system.

We’re beginning by using the CIIM to deliver data to our new website, the research documentation systems, and interoperable endpoints. In the longer term, the CIIM should be the single reuse source for all the Gallery’s collection-related data.

But opening up your data can reveal problems: for example, to join it up, you need a system of common identifiers, shared between the source systems. In theory, accession numbers should do this for object-related data. But identifiers need to be persistent – and our accession numbers aren’t. Objects are often recorded as loans, before they’re acquired and given a new number – and the new numbers are not always added to every system.

Different systems for recording internal locations each used different names for the same location; none of them referred to the space asset codes assigned by our Buildings Department. They do now.

Opening up your data can also identify opportunities to improve how your organisation works. When we needed to add the space asset codes to our room booking system, we found that no single person or department owned the system and its data.

When we tried to extract data from our archive management system, we found that the same nominally unique ID value was sometimes used thousands of times. The fixes required an upgrade to a version that had been released in 2012. It’s important to keep systems up-to-date.

For collection-related images where we don’t own the copyright – works still in copyright, or loans in – opening up our data has revealed the need for a central record of what we can do with each image.

Images of the collection are currently managed using a combination of structured filenames, rules and folders containing original and derivative files. The problem is how to tie derivatives back to their originals, and work out what we can do with them. The middleware can mitigate this to some extent, but the project has emphasised the efficiencies that a DAMS for collection images would bring.

So what benefits will we get from opening up our information? At the moment, much of our data is locked away in individual departments’ files and systems. We want everybody working with the collection to access all the information they might need about a painting – bibliographies, archive references, provenances, conservation histories, technical analyses, etc. – in one place. This would save a significant amount of staff time, and would empower our staff, opening up new opportunities to explore and conduct research on our collection. It will also save the time currently spent retrieving and delivering data for other people. This will be the focus of our next collection information project, which will build upon our middleware to create a digital dossier for every painting.

Development of the existing Collections documentation into a digital research resource … that would function as a ‘digital dossier’ for each painting

The National Gallery Strategic Plan: 2018-2023

Between 2016 and next month, we’ll have published three major catalogues; each has resulted in many changes to our knowledge about our collection. These changes need to be sent, in different spreadsheets, to the growing list of people who use our collection data. So – beginning with some of the bigger users – we’re talking to Google Arts & Culture about offering them an Elasticsearch API to our collection data; and we’re participating in ArtUK’s project to trial harvesting data directly from collections’ own systems.

We’ve already shared our data with academic research projects, notably IPERION CH, building a pan-European research infrastructure for heritage restoration and conservation; and CrossCult, connecting people digitally to historical artefacts in different places across Europe. And we plan to use our new endpoints to provide data to E-RIHS, the European Research Infrastructure for Heritage Science; SSHOC, providing social science and humanities data to the European Open Science Cloud; and the Immersive Renaissance project, constructing a layered and interactive view of the art and architecture of renaissance Florence.2 Our data will be available soon from data.ng-london.org.uk; we’re finalising licence details and will let the MCG list know as soon as it’s ready.

Opening up our data already means that we can contribute to the creation of large-scale datasets, keep our collections at the forefront of research, and extend the ways in which users engage with our objects. But, now we’ve laid the foundations: this is just the beginning.

Notes

- We use: Gallery Systems’ TMS as a collections management system; Axiell Calm as an archives management system; SirsiDynix’s EOS.Web as a library management systems; Extensis Portfolio as a DAMS for non-collection images; a bespoke SQL Server Collection Image database (‘CID’) to record metadata about collection images; structured folders and meaningful filenames to manage collection images; Artifax to manage room bookings (and therefore statuses); and narrative texts were held in our Umbraco web CMS but are being moved to an authoring system based on DokuWiki. [↩]

- See also the Cambridge University page about the Immersive Renaissance project. [↩]