A keynote lecture delivered as part of the week-long professional development course Det relevante museum 2014, organised by the Museene i Sør-Trøndelag and Kulturrådet, Trondheim, 22 October 2014.

Introduction

I’d like to begin by thanking the Museums of South-Trøndelag and Arts Council Norway for the invitation to speak today. I’d also like to thank you all for listening to me in English. I’m continually impressed by other people’s ability to learn and work with a highly irregular language, and embarrassed at my – and most of my compatriots – complete lack of ability to do the same for other languages.

In line with the theme of this course, I want to talk to you about the relevance of documentation in museums; or rather, the importance of documentation for museums.

I’d like to persuade you that documentation is crucial to everything that we do in a museum – although the fact that the documentation strand on the course was one of the first to be fully booked makes me think that I may have an easy time.

Before documenting objects, curators should first document themselves.1

First of all, in the spirit of thorough and self-aware documentation, let me say a little about me, and where I come from, to give you some context.

The Horniman Museum and Gardens is a surprising, eccentric, family-friendly attraction in Forest Hill in south east London. It has been open since the late nineteenth century, when the tea trader and philanthropist Frederick John Horniman first opened his house and extraordinary collection of objects to the local community. Since then, our collection has grown significantly and includes internationally important collections of anthropology and musical instruments, as well as an acclaimed aquarium and natural history gallery – all surrounded by 16 acres of beautiful Gardens offering breathtaking views across London.

Our vision is straightforward:

To use our worldwide collections and the Gardens to encourage a wider appreciation of the world, its peoples and their cultures, and its environments.

I am the Museum’s Documentation Manager: I run a small department of documentation staff on permanent and project contracts, as well as manage our librarian and archivist.

I reached the Horniman via a tortuous route: I trained as an art historian, writing a Ph.D. thesis on descriptions of works of art and architecture in late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century Italy.

Before that I worked as a journals librarian at the National Gallery, indexing articles and building my first relational database in an old DOS program called DataEase.

After finishing my thesis, I was asked to check the inventory of works of art at the Palace of Westminster, and to implement a computerised collections management system for them.

Since then, I’ve worked on various documentation, digitisation and humanities computing projects, before working for three years as Manager of Museum Documentation at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. I started work at the Horniman in early 2010.

Definitions

But before we start discussing documentation and museums in depth, it’s useful to know what we’re talking about.

So, what is a museum; or rather, what does a museum do? Luckily, I don’t need to come up with a definition for myself: ICOM, the UN’s International Council of Museums, has produced a neat, global definition of what a museum is and does. It says:

A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment.2

Whilst it would be possible to debate elements of the definition – are all museums non-profit? are they all open to the public? – I’m more interested in what ICOM says a museum does: it

- acquires

- conserves

- researches

- communicates, and

- exhibits

its objects.

So we know what a museum is and does. But what is documentation? Before I start to define it, I’d like to ask you all a question: who here does documentation? Please raise your hand. [pause] Thank you. That’s about half of you. It’s increasingly important, nowadays, that we can quantify what we do and how successful it’s been – so this is a baseline against which I can measure whether I’ve been able to persuade you how central documentation is to what you do.

Coming back to definitions of documentation, once again ICOM has come to my assistance. CIDOC, the Comité International pour la Documentation, which is one of ICOM’s international committees, has produced a very useful ‘Statement of principles of museum documentation’. This says:

Museum documentation is concerned with the development and use of information about the objects within a museum collection and the procedures which support the management of the collection.3

In other words, documentation does two things:

- Creates and looks after the information about the museum’s objects

- Ensures that the museum can account properly for its objects – makes sure that the museum can say what it owns and where it is, and makes sure that nothing can happen to the collections without being properly considered and authorised.

Why is documentation relevant?

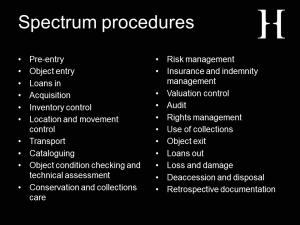

I think this already shows you why documentation is important to a museum, but I want to look at this in more detail; and I plan to do this using something you have probably heard about, and which – looking at the schedule for tomorrow – some of you will soon be very familiar with: Spectrum.4

Spectrum describes itself as ‘The UK Museum Collections Management Standard’, although as it is now being used or adapted for use in Belgium, Brazil, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Norway – and I think other countries are interested in using it – that seems a bit parochial. Its core content has not changed much since it was called ‘The UK Museum Documentation Standard’, and in both versions it provides a detailed conceptual framework which a museum can use to manage, and account for, its objects.

Usefully, it breaks this down into a series of individual procedures, and I want to use these procedures to show you how relevant documentation is to a museum’s activities.

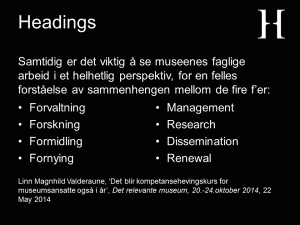

I’ll look at each of these in turn, using the headings which were used to announce this course:

- Management

- Research

- Dissemination

- Renewal

– although you’ll soon see that most procedures could happily sit under two or more of these headings.

Spectrum identifies eight of its twenty-one procedures as ‘primary procedures’, which any well-run museum should be using. In the UK, a museum cannot be officially accredited as a museum if it does not have the primary procedures in place and working effectively. But all the Spectrum procedures are important for a museum to function properly.

Management – forvaltning

As we’ve seen, documentation ensures that a museum can account properly for its objects – and what is this, if not management? Because Spectrum is a collections management standard, much of what it describes comes under this heading.

Pre-entry

The management and documentation of the assessment of potential acquisitions before their arrival at the organisation.5

Pre-entry is an interesting procedure, because in most museums it is usually part of the entry or acquisition procedures. (In passing, this is an important lesson about Spectrum: your museum’s procedures may not look exactly like those in Spectrum. That is not a problem; the key thing is that your procedures do all the things that the Spectrum procedures require, even if they do them in a different order or under a different name.)

If an object has not yet arrived in the museum, then this is the ideal point to ensure that the museum knows exactly what the object is, and that it has the resources to care for the object if it does acquire it. Proper pre-entry documentation will also establish when the object is due to arrive, and who is liable for transport costs, damage whilst travelling, and so on.

Object entry

The management and documentation of the receipt of objects and associated information which are not currently part of the collections.6 (Primary procedure.)

It’s vital that we record anything coming into the museum for many reasons, but the most important is so that we always know what objects we are responsible for at any one time, and who owns them.

If it’s done properly, object entry documentation can identify and record:

- who is leaving an object at the museum

- that they do actually own it, or represent someone who does

- what they intend the museum to do with it

- what the object is

- that its ownership is transferred to the museum if it is accepted for acquisition

- how long the museum is expected to look after it for

- what the museum can do with it if it’s not accepted for acquisition, and the owner doesn’t collect it – which stops you building up a backlog of objects which don’t belong to you and whose owners you can no longer find

- who is liable for what, if anything happens to the object whilst it’s in the museum’s care

It also provides the opportunity to record everything that the owner knows about the object: it’s better to capture that information as soon as the object arrives, than to have to go back to the owner at some later date – if you haven’t delayed it for so long that you can’t find them again.

Loans in

Managing and documenting the borrowing of objects for which the organisation is responsible for a specific period of time and for a specified purpose ….7 (Primary procedure.)

Related to object entry are loans in. Here, proper documentation again ensures that we know what objects are entering the museum’s care, why, and for how long; precisely how we are expected to look after them; who owns them; and who is liable for what if anything goes wrong. It should also help us manage the whole process, so that loans are arranged in a timely manner, and everyone has the information they need to do their work in good time, without last-minute panics.

Acquisition

Documenting and managing the addition of objects and associated information to the collections of the organisation and their possible accession to the permanent collections.8 (Primary procedure.)

The decision to acquire an object is one of the most crucial a museum can take, because it will be committing itself to use its resources to care for that object for the foreseeable future. It’s therefore vital that the impact of the acquisition is documented and understood before the decision to acquire is made (this falls under pre-entry); that the decision itself is clearly documented, so that the wrong objects do not enter the collection; and that there is a formal record of what objects have entered the collection, usually in the form of accession registers. As part of this, the museum needs to be able to prove, with documentary evidence, that it has actually acquired the object – in other words, that the owner was legally able to pass ownership of the object on to the museum – and that it has carried out all the checks necessary to ensure that the acquisition is ethical and legal: that the object has not been stolen, or excavated or traded illegally, that it was allowed to leave its country of origin, that it does not contain material from an endangered species, and so on.

As part of this process, the object will be assigned its unique number, and this will be physically marked on it if at all possible; we all know the huge problems that can be caused by objects which have lost their numbers. Indeed, I hope none of you have ever had to deal with a problem caused by poor acquisition documentation. If you have, you will understand just how vital it is that it is correct.

Inventory control

The maintenance of up-to-date information accounting for and locating all objects for which the organisation has a legal responsibility.9

Although it is not a primary procedure, I have always believed that inventory control should be: it covers not just a museum’s own objects, but also loans in; objects waiting to be acquired or accessioned; objects left by the public for identification; and support collections, which are all those objects which are not part of the collections, but are used for research or teaching or as display props. I hope we all agree that it’s absolutely vital for a museum to know what its core collections are; but it also has to be able to separate those out from all the other objects it’s looking after.

In fact, much of inventory control is documented in other procedures, such as object entry and exit, acquisition, loans in and out – and cataloguing, which we’ll come to in a few minutes.

Location and movement control

The documentation and management of information concerning the current and past locations of all objects or groups of objects in the organisation’s care to ensure the organisation can locate any object at any time.10 (Primary procedure.)

Even if you haven’t suffered from poor acquisition documentation, I’m sure you have, at some time, not been able to find an object that you’re looking for. You therefore know why location and movement control is vital to a museum. It should not just record an object’s current location, but also keep a trail of everywhere an object has been: if there is a problem, you need to know where to look, or who to ask.

Importantly, location and movement control should also ensure that the move was supposed to take place – that the person responsible for the object has said that it can be moved.

Transport

The management and documentation of the transport of objects for which the organisation is partially or fully responsible.11

If transport events are properly documented, you will know that a particular shipment has been properly planned, and is being carried out according to the museum’s or the object’s owner’s standards; that all the necessary restrictions – customs, security, CITES, cargo restrictions – have been checked, the paperwork is in order, and the shipment is legal and won’t be stopped by customs; and that the object is insured whilst travelling.

Conservation and collections care

The documentation and management of information about interventive and preventive conservation activities.12

Now I’m sure we’ve all heard the horror stories about objects that have not been conserved in the right way or by the right people. Conservation and collections care documentation helps prevent these accidents by ensuring that any treatment is properly authorised before it takes place. It also ensures that future curators and conservators know what was done to the object, when, by whom, and using which materials; and that any new information which has emerged from the treatment – for example, better identification of the materials the object is made of – are added to the object’s catalogue record.

Risk management

The management and documentation of information relating to potential threats to an organisation’s collections and the objects for which it is temporarily responsible.13

Risk management seems rather abstract, but it isn’t: it includes disaster planning – something London museums, in particular, are very aware of after the burning down of the Cuming Museum in Southwark, in March last year.14 Crucially, it also helps a museum avoid killing or injuring its staff: collections themselves can be dangerous: heavy, or sharp, or containing radioactive substances, or asbestos, or poisons – at the Horniman, a lot of our weapons are also poisoned, and we’re trying at the moment to understand what toxins may have been used on which objects, before we ask people to start getting them out of boxes and examining them.

Insurance and indemnity management

Documenting and managing the insurance needs of objects both in an organisation’s permanent collection and those for which it is temporarily responsible.15

Insurance is an area where practice varies hugely from museum to museum, with some museums either choosing or required not to insure their collections. But when insurance and indemnity documentation is in place, it should ensure that the collection is properly insured or indemnified to meet the requirements of the law and the museum’s own policies; that the insurance policies are checked and renewed when necessary so that the insurance doesn’t lapse; and that the museum has funds available to meet any commitments such as an excess or liability.

Valuation control

The management of information relating to the financial valuations placed on individual objects, or groups of objects, normally for insurance/indemnity purposes.16

In order to insure the collections, you need to know what they are worth, and you need that information to be up-to-date and available to the people who need it: in other words, your valuations must be properly documented. And they must also be managed, so that this very sensitive information is only visible to those who need it.

Audit

The examination of objects or object information, in order to verify their location, authenticity, accuracy and relationships.17

Audit is closely related to other procedures, such as location and movement control and inventory control. It ensures that the documentation a museum holds about its objects is correct and up-to-date. The most crucial information it confirms is an object’s location and condition, but it should cover all the information about an object, so that the entire collection is recorded up to the museum’s minimum standard, the information is correct and not outdated, and there are no undocumented objects in the collection. Where objects cannot be found, an audit procedure will say what steps need to be taken – and will document what steps have been taken for future staff.

Object exit

The management and documentation of objects leaving the organisation’s premises.18 (Primary procedure.)

Just as it’s vital to know what objects the museum is responsible for because they are on its premises, so it is vital to know which of your objects are currently not in the museum’s care – not just loans out, but also potential disposals, objects sent away for identification or conservation or research, etc. Object exit documentation tells you which objects are off-site, and should also ensure that you know when they’re coming back, where they are right now, who is looking after them, that they were actually received by whoever’s looking after them, that they are being kept in suitable conditions – and that they were allowed to leave the museum in the first place.

Loss and damage

Managing and documenting an efficient response to the discovery of loss of, or damage to, object(s) whilst in the care of the organisation.19

Despite all our best efforts to minimise the risks through careful documentation and collections management, accidents do happen; and loss and damage documentation will record what lessons were learnt from the loss of or damage to an object, as well as recording what steps the museum took in response to it, for example alerting the police to a theft, arranging conservation work for a damaged object, and so on.

Management and morality

So, much of documentation comes under the heading of management, and it focusses on three key areas:

- Knowing precisely what the museum owns and where it is.

- Related to this, being absolutely clear about who’s responsible (and liable) for the museum’s objects, and other objects in its care, at any particular time.

- And finally, managing the risks that those responsibilities and liabilities entail.

Documentation is therefore absolutely central to a museum’s operations and management: without proper documentation in all the areas I have just told you about, museums are at great legal, financial and reputational risk.

The Horniman Museum is funded by the UK Government, and one of the arguments I use to persuade my colleagues to document the collection, and to document it properly, is to imagine that something has gone wrong: an object on loan has been broken, for example, and the Horniman has had to pay a substantial sum in compensation. (I should emphasise that as far as I know, this has never happened.) I ask my colleagues to imagine that they have been called before a parliamentary committee to justify this grotesque waste of public funds: do they have the paperwork to prove, to the most awkward, aggressive Member of Parliament on the committee, that all necessary steps were taken to ensure that this kind of thing would not happen?

But in addition to protecting the museum, I would argue that we also have a moral duty to ensure that our museums are properly documented. Museums are usually funded by the public in some form – whether directly by local or national government, or simply by admission fees – and so they owe the public a responsibility to care for the assets – the objects – on which they spend the public’s money, and which they hold for the public benefit. Good documentation means that museums can tell the public what they look after on their behalf, and where it is; and can show them that their objects are treated with the care that they need.

But documentation is about more than management and public accountability. In recording where objects came from, the decisions taken when they were acquired, where they have moved to (on and off site), what conservation treatment they have undergone, what values they have been given, and any accidents that may have happened to them, documentation creates a valuable resource for: research.

Research – forskning

For example, management information, the fact that we acquired a large collection of objects directly from the Romanian government in 1957, and the documentation surrounding that acquisition, has fed directly into our current Revisiting Romania exhibition: it has become useful historical knowledge nearly 60 years later. So everything that I’ve spoken about under the heading of ‘management’ should also be regarded as supporting research. But there are a couple of Spectrum procedures that are more specifically about the act of researching a museum’s objects.

Cataloguing

The compilation and maintenance of key information, formally identifying and describing objects. It may include information concerning the provenance of objects and also collections management documentation e.g. details of acquisition, conservation, exhibition and loan history, and location history.20 (Primary procedure.)

Of course, cataloguing has a vital management role, ensuring that information is recorded that allows each object to be distinguished from other, similar objects within the collection. This used to be the role of the object description; increasingly, we are using images of the objects to tell them apart: nowadays, photography is a crucial part of cataloguing.

But cataloguing covers everything we know about the object – so the catalogue should contain all the information that has been created about the object under all the other procedures; or at least a way of accessing the information quickly and easily. Information that won’t be found elsewhere in the museum includes all the contextual information about the object: the people or organisations who made it, used it, sold it, owned it or are depicted in it or represented by it; places and excavation sites; historical and contemporary events; publications; cultures and peoples; dates or historical periods; materials and techniques; species; how it was used; and so on, and on, and on. I cannot emphasise too strongly: without this contextual information, the objects in a museum are meaningless and therefore useless. We have to know what they are, and where they come from, to understand them; and we have to understand them before we can use them.

In fact, my opposite number at the British Museum, Tanya Szrajber, delivered a keynote lecture at the CIDOC annual conference last month saying exactly this: the title of her lecture was ‘The collection catalogue as the core of a modern museum’s purpose and activities’.21 One of her key points was that none of the other procedures can take place without it: you have to know what specific object you’re dealing with at any one time, and you can’t do that without some basic descriptive, identifying information. And Freda Matassa said yesterday that nothing can take place without information about the objects.22

Object condition checking and technical assessment

The management and documentation of information about the make-up and condition of an object, and recommendations for its use, treatment and surrounding environment.23

I have included condition checking and technical assessment under research because it also adds to our understanding of an object, particularly how it was made – and that is part of the contextual information that gives our objects meaning. But knowing what an object was made of, and how it was made, is also vital if we are to care for it properly: it dictates the environmental conditions we must store and display it in, for example. And without knowing an object’s condition, we cannot handle it properly, or prioritise the treatment of the objects most at risk of deterioration.

In short, research-related documentation helps us to know as much as possible about our collections, and record the information in a way that ensures we can all use it.

Dissemination – formidling

And this is important, because, along with our responsibility to manage our objects on behalf of the public, we should also disseminate them: show them to people, and tell people about them.

Rights management

The management and documentation of the rights associated with the objects and information for which the organisation is responsible, in order to benefit the organisation and to respect the rights of others.24

One thing that helps us to do this is a clear understanding of who owns what intellectual property rights – most importantly copyright – in an object: we do not have the right to reproduce an object, and disseminate those reproductions, without the rights holder’s permission. If we do so, we are breaking the law. Basically, it’s as simple as that, although there are ways of negotiating the problems that this causes – but now is not the time to start discussing copyright law, unless you all wish to still be here at 9 o’clock this evening. Documenting rights management means that we know what we can and can’t do with any object, and whose permission we might need to seek to reproduce and publish it.

Use of collections

The management and documentation of all uses of and services based on collections and objects in the organisation.25

But by far the most important Spectrum procedure for dissemination is use of collections. The Spectrum definition goes on to say that it includes

… exhibition and display, education handling collections and the operation of objects, research and enquiries, reproduction and the commercial use of objects and associated documentary archives. Users include staff (and volunteers) or the public, whether in person, by letter, telephone or any other means of communication.

So ‘use of collections’ also includes publishing our objects, and putting them online and sharing them digitally, either on our websites, through social media, or via interoperable interfaces to other systems such as Europeana26 or the semantic web.

How does this relate to documentation? First, nothing should happen to an object without the museum’s permission: these procedures need to be established, and enforced, and the relevant authorisations documented and preserved.

Second, it is extremely useful to know how an object has been used in the past: this can tell us which are our most popular objects, or the best or least understood; it might suggest which objects need a rest, and prompt us to find some other objects in the stores which could work as well; and of course it helps us tell our managers just how hard we have been working making objects available to visitors and researchers, hosting visits to the stores, putting objects online, answering enquiries, and doing all those other things which may not be immediately visible but are vital to getting our collections out into the world.

Third, documenting the use of collections means also capturing information which emerges from that use: which objects were on display in which galleries, and when; the results of scientific investigation or the research of an expert who visits the stored collections; the reactions of a musician who plays one of our instruments (and perhaps a recording of their performance for use on our website?); or the reactions and knowledge of a member of the source community from which we obtained an object half a century ago.

Loans out

Documenting and managing the loan of objects to other organisations or individuals for a specific period of time and for a specific purpose ….27 (Primary procedure.)

One aspect of use of collections is of course display and exhibition, and external exhibitions are facilitated by loans out – but so too is research or, in the case of a handling collection, perhaps, education. So loans documentation contributes to our use of collections information; but it will also ensure that we know where our objects are, who is responsible for them, and when they are due back; that the borrower has insured them, and committed themselves to caring for them properly; and what must happen – and who is liable – if anything goes wrong

Future use – and money

As you’ve no doubt realised, dissemination-related information, too, can become historical information: to use our current Revisiting Romania exhibition again, the interpretation talks about our objects’ roles in our 1957 exhibition of Rumanian Folk Art. And no doubt our records of what was displayed in Revisiting Romania, and how, will in turn be used by future curators as they, too, come to research or plan exhibitions of our Romanian objects.

Some of these activities can also earn a museum money directly, such as the sale of images and merchandise based on the collections; or charging for lectures, visits to the stores, handling sessions, or exhibitions and, as Freda Matassa showed us yesterday, loans.28 All of them, by showing how effectively the museum is working, should help to attract funding. But none of them are possible without documentation: you have to know what objects you have, why they’re important, and where they are, before you can use them.

Renewal – fornying

Money and funding are vital to museums’ renewal – by which I mean, their evolution and development into more effective, sustainable organisations better able to face the future.

Deaccession and disposal

The management of disposal (the transfer, or destruction of objects) and of deaccession (the formal sanctioning and documenting of the disposal).29

You might ask: how would disposing of a museum’s collections make it more effective? As I’ve said already, museums are committed to spending their often limited resources on the care of their collections; it therefore makes sense for them to be sure that they are spending those resources on objects which are central to their particular purpose, and which they are actually capable of looking after properly. A good pre-entry procedure means that new acquisitions will match those purposes; but not all the older collections necessarily do. A well-planned programme of reviewing the collections, and disposing of objects which do not fit the museum’s central purposes and, crucially, which could be used more effectively or cared for better elsewhere, means that the museum no longer has to spend its resources on objects that do not help it fulfil its core aims. Objects may also be disposed of for moral reasons: for example, the return of items spoliated during the Nazi period to their former owners or their descendants, or the return of human remains to their source communities.

Disposing of an object is of course a very serious step to take, and there are many dangers, both reputational – the public may feel badly let down by a museum that disposes of objects which they believed were going to be preserved for eternity; and legal – for example, former owners may have some claim over the museum which prevents it from disposing of the objects they gave or sold to it. And disposing of an object for the wrong reasons can have serious consequences.30 Disposals must be for the museum’s benefit, and ethical – and there are clear published guidelines to be followed when disposing of objects. All of which means that the process must be followed scrupulously – and all the steps taken conscientiously documented, because disposal will be subject to significant public scrutiny, and the museum must be able to show that it has followed them to the letter.

Retrospective documentation

The improvement of the standard of information about objects and collections to meet SPECTRUM Minimum Standards by the documentation of new information for existing objects and collections.31 (Primary procedure.)

A key way of finding out whether your collections match your museum’s core aims is to review them: to see what objects you have and, crucially, to ensure that the documentation you have about them – particularly, but not exclusively, the catalogue records – is correct, and meets the minimum standards you have laid down for it. The process of ensuring all your documentation is up to standard is called ‘retrospective documentation’, and without it older museums, in particular, may have great difficulty knowing, finding, and understanding what they own.

The relevance of documentation

With retrospective documentation, we have reached the last of the Spectrum procedures. Now that we’ve gone through everything covered by museum documentation – which I hope covers pretty much everything a museum does – I’d like to pause and see how well I’m doing. I’d like to ask you again: who here does documentation? Please raise your hand. [pause] Well, that seems to be fewer than before; clearly I’m doing something wrong.

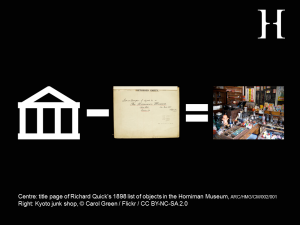

So far, I’ve done my best to persuade you that documentation is not just relevant, or even important, but vital to a museum. One of the best summaries of this is a statement which I’ve heard attributed to Nick Poole: ‘Documentation is the difference between a museum and a junk shop.’

So if we return to our ICOM definition of a museum, and what it does – acquires, conserves, researches, communicates, and exhibits – something crucial seems to be lacking: documentation. I’d therefore like to propose another summary of what a museum does, and once again, I will shamelessly steal someone else’s definition: this list comes from Tanya Szrajber’s lecture on the importance of the catalogue, which I mentioned earlier:

- Documenting the collection

- Care and preservation of the collection

- Developing the collection

- Providing access to the collection: physical and virtual

- Researching and interpreting the collection

- Developing and sharing expertise

- Engaging communities and the public generally32

The invisibility of documentation

Now, I’d like to tell you a very short story. About a year ago, I went into a national museum in London, and there I saw a collecting box, for visitors to give money to the museum. (Stupidly, I didn’t take a photograph of it.) It offered visitors a choice: did they want their money to go to the museum’s conservation department, or to its learning department?

I expect you know now what my response was: ‘Neither! I would like my money to go towards documentation.’ But why wasn’t documentation a choice? This is an important question, at least in my experience of UK museums: a museum cannot function without documentation, yet it is often under-resourced, carried out by a small department (if it has its own department at all – increasingly it does not), and often relying on other people – for whom it’s often not the first priority – to carry out processes and procedures. Why are we so often under-resourced? Because we are not visible

As a first step to investigating this problem, I started a discussion33 on the Collections Trust’s LinkedIn group for collections management – a very useful resource which I’d strongly recommend to any of you who are not yet members.34 I began by asking for pithy descriptions of what documentation is and why it’s important, and was delighted by the response. Here are some of my favourites:

Louise Newell said that ‘Documentation is how we make sure we know what our objects are and where on our sites we can find them!’ Ron Twellman was similarly practical: ‘Documentation is the lubrication that keeps a museum running smoothly and efficiently. Without it things would quickly break down.’ For Sheila Perry, ‘Documentation is boring until you can’t find something – then it becomes vitally important!’ Victoria Merriman also focussed on what happens when documentation breaks down: ‘An object without provenance is simply interesting or inspiring. Without location, owner, or inspection records it can be troublesome.’ And for Ann Cejka, things going wrong was central: ‘For me, documentation = $. Particularly in a disaster situation. … There will always be people who think documentation of collections doesn’t matter – until one day it really does.’

Tom Bilson emphasised the importance of knowing what an object is: ‘Portrait of don’t know, by someone or other, donated in can’t remember: that’s why museum documentation is important.’ Michaelle Haughian also focussed on the importance of contextual information: ‘Documentation is the story: without a story the object is pretty much meaningless – at least in human history departments.’ And Jackie Hoffman Chin brings us back to the importance of all that information when managing collections: ‘Documentation. The first step in accession. The first look at conservation. The first consult in writing a tourguide.’

Like Jackie Chin, Richard Ferguson stressed the importance of documentation when disseminating our collections: ‘Documentation enables us as custodians of our material culture to know what we have got, know something about it, know where it is so we can tell stories that inspire us all.’ Douglas McCarthy was even pithier: ‘Good documentation enables collections care, understanding and outreach, now and in the future.’

Peter John Natividad was also thinking about the importance of documentation for the future: ‘Documentation is a collective/shared museum team effort and all information should not die with you.’

Some people chose to cut right to the heart of what museums are for. Nick Poole, in the middle of a long post, reminded us that ‘… societies need to know where they have come from to understand where they are and where they are going, and it is documentation that enables us to do that.’ For Angela Kipp, ‘Losing your memory means losing yourself. Without documentation humanity loses its memory.’

And perhaps my favourite came from Barbara Palmer: ‘I find out what we have acquired … and make sure each acquisition is in the database. I oversee transcription of original descriptions, and record current locations if I can. I uncover hidden treasures and make them accessible. I feel like I have the best job in the world.’ (Sometimes I need to be reminded why I’m doing the job I do.)

Specialisation

But the LinkedIn post also provoked a broader discussion, and I’d like to share a couple of aspects of that discussion with you today, because they relate very much to this question of why we’ve reached the point where documentation is so difficult to see.

Like so much museum work, documentation was originally one of the things that curators did; and when it consisted of registering an acquisition, creating index cards for it, pulling one’s research into a history file, and updating a location card when the object moved, it was easier to incorporate it into one’s day–to–day curatorial work. But then computers arrived, and they became the preserve of specialists – understandably, if you look at a system like Mimsy XG, which we use at the Horniman: there are perhaps 3000 different, discrete units of information in there, and to configure it, maintain it, and keep the data consistent is a specialist job which the vast majority of people who work in museums simply wouldn’t want to do. So documentation jobs were created to manage the information, and to make sure that the procedures drawn up in Spectrum over the last 20 to 30 years were being implemented and tied into the computerised information: suddenly, there was a new sub–discipline within museums.

The last two or three decades have indeed seen a huge increase in specialisation in the museum world: there are many other specialists doing some aspect of the work that used to be done by curators – and there are far more of them now, than there used to be curators. We should, I think, be grateful for this; but it has had a couple of consequences.

First is that we have far more people relying on our documentation, so it has to be good – we can’t rely on people’s personal knowledge filling in the gaps – and it has to be easily accessible. This is something that Gareth Salway, the Documentation Manager for Bristol’s Museums, Galleries and Archives, said in a recent interview in the Museums Journal:

When I first started in documentation, records were kept so that curators knew roughly what objects were and where they were kept.

Twenty years on, a whole range of people, from learning and communities to marketing and, most importantly, our audiences, want direct access to our records in as high a quality and as quickly as possible.35

Second is the fact that, despite this specialisation, more and more people are doing documentation. This is what I was trying to show in the first part of this talk; and the people contributing to the LinkedIn discussion were called ‘curator, documentation officer, collections information systems manager, content manager, access officer’, and so on. This causes several problems.

One is that the people who do documentation don’t necessarily know that they’re doing it. A second is that they may not have the necessary skills to do it well: it requires a slightly obsessive degree of attention to detail – a badly-placed full-stop can be enough to stop a system working effectively; and it also needs an insistence on taking the time required to do a job thoroughly and properly at the beginning, rather than doing just enough to meet your immediate needs and hoping to return to something later.

Another is that, in larger organisations at least, the responsibility for documentation remains with the small group of people who actually have ‘documentation’ in their job titles – but they do not manage the people who do much of the day-to-day documentation work. They have great responsibility, but not the power to go with it – and this can make it difficult to ensure that the people who do the documentation day-to-day have those particular skills, and do it properly. At the same time, documentation is seen as only being what ‘documentation’ people do – primarily something technical, or a support service – not the all-pervasive, enabling system that it really is.

Image

As well as this split between the people who may be doing documentation, and the people who are responsible for it, its very name can be a problem. Jude Dicken, the Documentation Officer at Manx National Heritage, said in the Museums Journal:

Like many museum staff working in this area, I dislike the title ‘documentation’. As soon as you say it, people glaze over and start thinking of index cards and admin.36

But this doesn’t necessarily reflect what documentation staff do day-to-day. John Holt identified this problem when he introduced his recent set of interviews with documentation workers in the Museums Journal:

Practitioners [of documentation] can pinpoint a Poussin at 200 feet, translate ancient texts or convoluted computer jargon into something understandable or even rough it out in the (database) fields and (archaeological) trenches.

More excitingly, some are quite promiscuous, at least with their data, they are in charge of exciting-sounding projects such as Bioblitz and one even received formal firearms training in order to find out how to handle a gun properly. Not bad for a workforce that’s often stereotyped as desk-bound data monkeys.37

As Jude said:

I feel very much part of a collections knowledge management strategy that sits across four areas – access, care and conservation, collections conservation including disposal and, finally, information.38

So what should we be calling ourselves? This is a question that’s on my mind at the moment: I was given the Horniman’s Library to manage a few months ago, and as I’m already responsible for documentation and our archive (and was at one time overseeing our records manager), ‘documentation’ doesn’t seem adequate any more. Perhaps ‘collections information’? ‘Collections knowledge’? But neither seems to cover that element of accountability which is so important to documentation. I still don’t know, and I’d be grateful for any suggestions.

Should documentation be visible?

All of this goes some way to explaining documentation’s invisibility. In museums, we show off our exhibitions, displays, interpretation, and websites – but visitors can’t see the infrastructure used to create them. When do we ever say ‘this exhibition was brought to you using the quality data in our collections management system’?

But is this a problem? The LinkedIn discussion broke down into two groups: first, those who felt that it’s not worth raising documentation’s profile to the public, because it’s part of a process that leads to public outputs like displays, exhibitions, engagement or learning events, and those end results are what’s important; and second, those who thought that it is worth publicising what we do for its own sake.

Some people thought that documentation was primarily of interest to other museum people, and the public don’t need to see how it works. Nick Poole argued against dividing museums up into separate activities, saying that we should focus on the end result instead. He made a good point when he reminded us that there’s been a long–standing culture clash between documentalists, who tend to be systems thinkers, and our colleagues who are, as he said, ‘value–driven creative people with a strong set of social values’. This means the documentalists have had to explain the value of documentation in ways that the value-driven creative people can appreciate: in terms of its end users. This pressure is increased, in the UK at least, by a political climate where we are constantly being asked to justify what we do in tangible, measurable and visible ways – in other words, largely in terms of visible, public outputs, not the infrastructure that supports them.

But in this climate, can we afford to ignore documentation? In the UK and, I expect, around the world, publicly–funded museums are under great financial pressure: we’re expected to do as much work as we’ve always done – if not more – with less and less money. As a result, we need to look more widely for funding, even for our core activities. So the way that funds are allocated becomes a crucial question. Angela Kipp pointed out that ‘people decide to fund what they know, see and take part [in] in museums (educational programmes, tours) and not something that is hard for them to imagine, because it needs explanation ….’

And of course we do talk about what goes on behind the scenes: at the Horniman Museum, for example, on our website we make a great deal of our Conservation department’s work; and we’ve recently been tweeting furiously about the object selection and installation of our Revisiting Romania exhibition. Like that collecting box, this shows that we do publicise our behind the scenes work – but only certain parts of it.

I think this is the fundamental problem: if you don’t know something exists, how do you know that it’s important, let alone that you could fund it? And so we need to think not just about making documentation visible to the public, but also to our senior managers, our trustees, and our funders.

This is the crux of the matter: in the current climate, we are being asked to do more and more with less and less. Poor documentation stops us from working as efficiently as we might, and so we cannot give our collections the support they need. We have to work as effectively as possible, and really good documentation enables that; but we cannot provide it if it is not adequately resourced; and it will not be properly funded if people do not even know it exists.

Raising the profile

But we need to go beyond telling people simply that there is such a thing as documentation. A few months ago, I was talking about the difficulty in funding day–to–day documentation work with my Director, and she said something which is very important when we’re telling people about documentation: ‘you need to tell the story’. As well as saying that documentation’s important, we also have to say why it’s important.

This means that we need to do some explaining. We can start publishing more about what we do, in blogs and other outlets. As a result of the LinkedIn discussion, I was asked to write what turned into a very long blog post for the Registrar Trek website;39 I was interviewed for the John Holt article in the Museums Journal that I’ve been quoting from;40 and I was asked to write a piece for the Museums & Heritage Advisor website.41 I’ve also been trying to publish short articles about aspects of documentation on my own website.42 And of course I’m here today, talking to you. The point here is not to boast about what I’ve been doing recently, but that there are already vehicles we can use to try and get our message across.

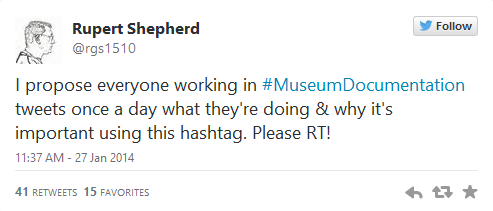

Another medium we can use is Twitter. I’ve suggested that everyone working in museum documentation who has a Twitter account should tweet what they’ve been doing each day, and why it’s important, using the hashtag #MuseumDocumentation. This is not always easy: I’ve found the experience of saying why what I do matters, in a new way every day, quite challenging – particularly when I’m working on the same task for days at a time, or tweeting again about chairing the acquisitions committee – but the challenge is also making me think more about why I do do things. And other people have been joining in as well.

Perhaps not as often as I’d like – people seem to post when they’ve done something particularly unusual or interesting, rather than every day – and they usually say what they’ve been doing, but not why it’s important; but it’s a start, and I will keep encouraging them. (I also know that my Director follows me on Twitter: there’s nothing like going straight to the top.)

All this is well and good – but it is really only talking to people within the sector, and to those colleagues, family and friends who follow us on Twitter. How do we get our message across to the public as a whole? One suggestion which came up during the LinkedIn discussion was that we talk about documentation when we are showing people what goes on behind the scenes at the museum. I’m pleased to say that my colleagues in collections management at the Horniman, who have been running public visits to our stores for some years now, have always made of point of doing this.

In the end, we need to work with the colleagues who manage our organisations’ public faces and persuade them that, without documentation, they would have nothing to publicise – and so it’s in their own interests that people understand what documentation is, so that it’s properly resourced into the future. We need more tweets like this to come from our museums’ official accounts, not from our personal ones.

I hope that, today, I’ve given you the resources and the encouragement that you need to persuade your colleagues that, although it’s often hidden from view, documentation affects everything a museum does, and without documentation, a museum’s objects are meaningless; that documentation is not just relevant, but vital to a museum; that documentation must therefore be cherished and properly funded; and that we need our colleagues’ help to ensure that as many people as possible understand what it is and why it’s not just relevant, but important for museums.

Notes

- Keletso Gaone Setlhabi, ‘What is the object name? The conflict between vernacular and official languages in the documentation of collections’, Access and understanding: networking in the digital era, CIDOC 2014 Annual Conference, Dresden, 6-11 September 2014. [↩]

- ICOM, 2007, http://icom.museum/the-vision/museum-definition/, accessed 5 October 2014. [↩]

- CIDOC, Statement of principles of museum documentation, version 6.2, June 2012, section 1.1, http://network.icom.museum/fileadmin/user_upload/minisites/cidoc/DocStandards/principles6_2.pdf, accessed 5 October 2014. [↩]

- Alex Dawson and Susanna Hillhouse eds, Spectrum: The UK Museum Collections Management Standard, version 4.0, London: Collections Trust, 2011, accessible via http://www.collectionstrust.org.uk/collections-link/collections-management/spectrum/the-spectrum-standard, accessed 28 August 2015. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 14. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 17. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 20. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 26. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 30. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 33. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 36. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 49. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 52. [↩]

- BBC London News, ‘Southwark museum fire: 500 artefacts saved but roof destroyed’, 26 March 2013, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-21936775, accessed 4 October 2014. In fact, the building was gutted, but the bulk of the collections survived. [↩]

- Dawson & Hillhouse, Spectrum, p. 55. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 58. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 60. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 75. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 84. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 40. [↩]

- Tanya Szrajber, ‘The collection catalogue as the core of a modern museum’s purpose and activities’, Access and understanding: networking in the digital era, CIDOC 2014 Annual Conference, Dresden, 6-11 September 2014. [↩]

- Freda Matassa, ‘The relevant museum’, Det relevante museum 2014, Trondheim, 20-24 October 2014. [↩]

- Dawson & Hillhouse, Spectrum, p. 43. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 64. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 68. [↩]

- http://www.europeana.eu/, accessed 29 October 2014. [↩]

- Dawson & Hillhouse, Spectrum, p. 78. [↩]

- Matassa, ‘The relevant museum’. [↩]

- Dawson & Hillhouse, Spectrum, p. 88. [↩]

- BBC Northampton News, ‘Sekhemka statue sale: Northampton Council violated trust”’, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-northamptonshire-29450744, accessed 4 October 2014. [↩]

- Dawson & Hillhouse, Spectrum, p. 93. [↩]

- Szrajber, ‘The collection catalogue’. [↩]

- Rupert Shepherd, ‘The invisibility of documentation’, https://www.linkedin.com/groupItem?view=&gid=3280471&type=member&item=5813315842561044481&trk=groups_search_item_list-0-b-ttl, accessed 29 October 2014. [↩]

- https://www.linkedin.com/groups?gid=3280471, accessed 29 October 2014. [↩]

- Gareth Salway, quoted in John Holt, ‘The documenters’, Museums Journal, vol. 114 no. 5, May 2014, pp. 24-29, http://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/features/01052014-the-documenters, accessed 29 October 2014. [↩]

- Jude Dicken, quoted in Holt, ‘The documenters’. [↩]

- Holt, ‘The documenters’ (my emphasis). [↩]

- Dicken, quoted in Holt, ‘The documenters’. [↩]

- Rupert Shepherd, ‘Museum documentation: a hidden problem or something to shout about?’ Registrar Trek, 2 May 2014, http://world.museumsprojekte.de/?p=4023, accessed 29 October 2014. [↩]

- Rupert Shepherd, quoted in Holt, ‘The documenters’. [↩]

- Rupert Shepherd, ‘Documentation: backlogs, reviews and hashtags’, Museums + Heritage Advisor, 31 July 2014, http://www.museumsandheritage.com/advisor/news/item/3543, accessed 29 October 2014. [↩]

- Rupert Shepherd, ‘Category archives: documentation’, https://rupertshepherd.info/category/documentation, accessed 29 October 2014. [↩]