Last Saturday, 20 December, I went back to my old school, Loretto, for the first time in 29 years. I was drawn not by any great feeling of nostalgia for my schooldays, but because the story of my great-grandfather, Archibald Henry Buchanan-Dunlop, was the impetus behind events that were being held there to mark the centenary of the Christmas truce on the Western Front. These culminated in the unveiling, in the school chapel, of a window made by Kate Henderson commemorating the truce and my great-grandfather’s role in it. But what, exactly, was his role?

Announcing the commemorative events, the Edinburgh Evening News described Buchanan-Dunlop as ‘the man who was said to have “stopped the First World War” … it is said he led the men over the top to revel in some festive cheer with the enemy.’ According to the Deadline news agency, he was ‘instrumental in the famous “Christmas Truce”’.1

But when I read a standard account, Brown and Seaton’s 1984 Christmas Truce, which included Buchanan-Dunlop’s letters amongst its many sources, the picture appeared rather different: he had certainly sung carols (from the programme of that year’s Loretto end-of-term carol concert), and met and swapped tobacco and papers with the Germans – but nothing gave me the impression that he had been instrumental in bringing the truce about.2 Indeed, Brown and Seaton show that the Truce was largely a spontaneous affair, extending over at least twenty miles of front line and involving numerous regiments on both sides: hardly something that could have been instigated by a single company commander.

So, being a conscientious historian, I thought I would go back to the primary sources: Buchanan-Dunlop’s letters home, and the contemporary press reports of his participation in the truce. This essay aims to show what happened to him over the Christmas of 1914 (not just during the truce) in his own words, and looks at how his apparently unexceptional participation was seized upon in the press, and then by his superior officers.

Before the war

Born on 26 September 1874, Archibald Henry Buchanan-Dunlop (known as Archibald), was educated at Loretto School, outside Edinburgh, from the age of 12, leaving in the summer before his 15th birthday in 1889.3 He went on to Sandhurst, and was commissioned into the Royal Berkshire Regiment in 1894. He married Mary Agnes Kennedy on 3 March 1900, a few days before sailing for South Africa and the Boer War, during which he served as a Railway Staff Officer. He joined 2nd Battalion The Leicestershire Regiment as a captain in 1903, and in 1905 was seconded to the militia, serving as the adjutant of 3rd Battalion The Lancashire Fusiliers. He also served as Director of Army Gymnasia.

Buchanan-Dunlop retired from the regular army in 1909, aged 34 or 35, and returned to Loretto to teach gymnastics and drawing, and to command the school’s Officer Training Corps (OTC). On the outbreak of the First World War, he was mobilised and appointed to Headquarters for embarkation duties.4 He sailed to France on 1 November,5 and joined the 1st Battalion of his old unit, the Leicestershire Regiment.6 By now, he was 40 years old, and had three sons: Robert Arthur, born in 1904; Archibald Ian (my grandfather), born in 1908; and David Kennedy, born in 1911.7 He already had fifteen years of service as a regular officer under his belt.

Before Christmas

Buchanan-Dunlop wrote regularly – often daily – to his wife Mary from France, giving accounts of his day-to-day life in the trenches and behind the lines.8 His letters often contain news of and thanks for letters and parcels containing food and warm clothes sent by his friends and extensive family (he had four sisters and three brothers), as well as lists of things he needed (usually more warm clothes, note paper, candles – and strings for a violin he had bought in France). They show him as a conscientious and professional officer, concerned for the morale and spiritual welfare of his men, a keen amateur musician, a committed Christian, and devoted to his wife and children.9

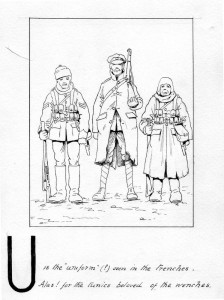

Archibald Buchanan-Dunlop, U is the “uniform” (?) seen in the trenches, from the published version of An Alphabet from the Trenches

On 21 November, Buchanan-Dunlop moved up to the front line between Touquet and the farm at Flamengrie;10 he wrote to his wife Mary on 22 November 1914:

Last night, marching up here (you have to come up at night or you get picked off) I had a narrow shave, the enemy, who are only a couple of yards from our trenches, fired, presumably at the sound of our marching, & just missed my head. The bullet went into the bank behind me.

Captain Tidswell, the adjutant,11 came up to the farm we were in, as I was writing to you; & told me that the Colonel12 wanted me in the trenches at once to take command of one of the companies, so I am now snugly ensconced in the firing line, writing to you by the light of a candle. … Tell Og13 I am a Major, not a Captain. – in the Leicestershire Regt.14

Notwithstanding his close shave, Buchanan-Dunlop wrote to Mary on 25 November:

The Colonel is very cheery & jolly & we are all very well. The food is excellent & plentiful, but is all brought in of course, at night. No rest of course from bullets, but nobody minds them. Dear little wife, don’t you worry a bit about me. I’m happy & well, & quite enjoying it as long as my Company is all right (& we’ve had no one in the company hit for a long time) I’m very careful & insist on my officers & men being the same. If it’s one’s duty to take a risk, why you take it; but if it’s not necessary, I consider it wrong not to be as cautious as possible. I don’t mind how much I rough it; it’s good for me & I feel really most awfully well, and what Aunt Emma says15 is quite true.16

As C Company commander and second-in-command of his battalion, Buchanan-Dunlop had just been promoted major: in a letter to his wife of 1 December, he asked her to send him a major’s crowns and braid for his uniform; he received them two and a half weeks later, thanking her in a letter of 17 December. The Regiment had also had a visit from the King whilst out of the line at Fleurbaix, described in a letter from Buchanan-Dunlop to his wife, 2 December 1914:

Secondly we have been reviewed this afternoon by The King!! Wasn’t it good of him to come out & buck us up. I’m so glad we happen to be one of the Regiments out of the trenches when he came. He was so nice & took notice of each officer. The Prince of Wales was with him. The King is looking older & more careworn, no wonder, poor man. Isn’t it sporting of him to come out?

We marched of course to a town some miles behind our billets,17 for of course we had to be well out of range of every gun the Germans have. Aeroplanes were out & about all the time keeping a good look out. I got on to my horse for the first time – you know all company commanders are mounted now – also I am at present second-in-command – He is such a big beast, I can hardly reach the stirrups. A chesnut [sic] with hogged mane & long tail. Robert18 will tell you all about him for I’ve written to him, & described my steed.

Early in the month, Buchanan-Dunlop was already thinking about Christmas and the celebrations at Loretto, writing to his wife on 8 December:

What wouldn’t I give just to spend Christmas day with you & our little boys.… I shall miss the Carols in Chapel this year & the Christmas anthems. You don’t really know how fond you are of them till you’ve got to do without them.

The Battalion went back into the line from Rue du Bois to La Grande Flamengerie on 11 December, relieving the West Yorkshire Regiment,19 and Buchanan-Dunlop’s company seem to have been posted to a particularly dilapidated section of trenches, described in a letter to his wife of 12 December, in which he also sent ‘Thanks for sending Loretto reports’: he was glad to receive news of the school. He seems to have been about 1 mile north-east of Bois-Grenier, and was probably facing the German 107th, 139th and 179th Infantry Regiments, all Saxon, to his left; and the 15th and 55th Westphalian Infantry Regiments to his centre and right.20 The cold, and lack of water for washing or shaving, seem to have been the most uncomfortable aspects of trench life – along with the mud. He wrote to his wife on 23 December:

Last night was a jolly night, bright stars & no rain, & my trenches were getting quite clean, but this morning early, snow began to fall, & they are getting quite beastly again. However, now they have cleaned up a bit, & the snow has stopped, so if only we could get a little frost, we’d soon have them fairly passable.21

Christmas and the truce

Buchanan-Dunlop’s initial account of the Christmas truce is quite short, and contained in a letter to his wife, written on Christmas Day 1914:

Even out here this is a time of peace & goodwill. I’ve just spent an hour talking to the German officers & men who have drawn a line halfway between our left trenches & theirs & have all met our men and officers there. We exchanged cigars, cigarettes, & papers. They are jolly, cheery fellows for the most part, & it seems so silly under the circumstances to be fighting them. Firing has practically stopped, and it’s only when our men start repairing wire entanglements that they send along some warning shots. Last night a select band of officers & men sang carols to them, & they did ditto. That Loretto concert programme, with the words of the carols, was most useful to us.22 I got it, & your letters in 3 days, which is a record.… There is a hard frost, & everything is white & Christmassy, but cold, which personally I like.… I’m going to try & have a service for men off duty this afternoon & as there is a post out this afternoon, I shall be busy censoring letters, so can’t write you a long one today.23

On Christmas Eve, as far as we were concerned, we was still at war, but in the evening on sentry-go we heard singing from Jerry.… And our Buchanan-Dunlop who come to us as Battalion Commander, he kind of led the singing!

Interviewed in 1981.24

Christmas Eve found the Battalion trenches covered with snow, and a brilliant moon lit up No Man’s Land and the enemy trenches. After dusk the sniping from the German trenches ceased and the enemy commenced to sing; their Christmas carol grew louder as their numerous troops in the reserve trenches joined in, and eventually ended with loud shouts and cheering. ‘A’ Company of our Battalion then began a good old English carol, the regiments on right and left joining in also, and this was received by the enemy with cheers and shouts of, ‘Good! Good!’

On Christmas Day snow fell heavily, and, as the enemy did not snipe when the men exposed their heads, several of ‘B’ Company got out of their trench and stood upright in full view of the enemy; they were surprised to see the Germans do likewise, waving their hands and shouting in broken English. Orders were given by the Commanding Officer for sentries to be posted on the alert in case the enemy attempted any treachery, and the remainder of the Battalion, quick to take advantage of the opportunity, set to work repairing the trench parapet and collecting wood for fires. At dusk the sentries manned the parapet as usual, but the enemy remained quiet, all except his artillery, who continued to shell the back areas. That night the ration parties were again subjected to the glare of the searchlight on reaching the wood, and, expecting a volley of bullets, the men threw themselves flat, but the enemy infantry did not fire, and after arriving safely back with the rations, etc., the troops gave the Germans a rousing cheer!

Next day rain fell, thaw set in, the trenches collapsed during the day, the enemy recommenced to snipe and shell, Christmas was over and they were back to business. The trenches by this time were in a shocking state in places, owing to the sides falling, being here and there almost as wide as a country lane, with scarce any cover from the enemy snipers.25

There is more news of Christmas and Boxing Day festivities, and of a truce further along the line, in Buchanan-Dunlop’s letter to Mary written on Boxing Day:

I must begin a letter to you tonight. I’ve had quite a cheery Boxing Day: Hard frost & bright snow. I had some cake & a glass of Madeira & a chat, with the Colonel this morning; & Buggins26 asked me to lunch with him, as he had had a turkey! sent him & mince pies. He lives a good way behind us, as he is in Reserve with his Company.27 I had a tremendous lunch & was half comatose in a chair by his fire (unheard of luxuries when Colin suddenly came in.)28 I was glad to see him. It appears that he is about 5 miles or more to our right, & having a day off – for the Wurtembergers in front of him had agreed to an informal suspension of hostilities – had set out to find me, not knowing my Brigade. How he managed it I can’t think, but he found my dug-out and was re-directed to A company. He was so cheery, & looking very fit & well & awfully clean & neat. How he managed

itthat, too, I can’t think. He was much struck by my appearance I think, & no wonder, for I was in a waterproof, mostly clay, & had my Balacklava helmet on with a bit of Jean’s29 holly in it, & my moustache & beard are not tidy, & I’m not clean. He stayed about half an hour with us. I’m so glad we have found each other at last.Then this morning I got my Christmas Box from Princess Mary – a card, a pipe, & an embossed box in plain metal with tobacco and cigarettes in it – lastly & most important I got two letters & a letter-card from you, dated Nov. 10 – Dec 21 – Dec 23. The first had been to the Royal Warwicks why I don’t know. So you see my darling I’ve had quite a jolly day. – The enemy on our left – Saxons – are still out hobnobbing with our fellows, but the folk opposite us – Prussians – are very vicious indeed.30 It has begun to snow now – horror! I shall send you my Christmas cards from the King & Queen & Princess Mary – you might get little frames for them my sweetheart.

… I managed a little Christmas service for my company yesterday. I had to have three, one on the right, then move to the centre, then one on the left. I just had a few prayers, read them the Christmas story from St Luke, & had some hymns. Mother sent me a lot of St John’s gospels for the pocket, & they have hymns at the end. Please tell her how useful they have been and how much the men liked it. The General31 happened to come round just as the last one was going on, & said it was awfully nice. He had come down rather angry over the informal cessation of hostilities but seemed to be quite soothed by the hymns. – You’re not forgetting a prayer book are you my darling – I do feel so sorry for my men, only two in the company of 230 ever read a Bible, & no chaplain comes near the trenches. They never are reminded by anyone of God or the hereafter, & I feel it a duty to have a service on Sundays, now that I have “broken the ice” & found out that they will come. It is a feeble effort, but still something that one can do for Him who has given us so much.32

We learn a little more about what happened on Christmas Day from a letter to Mary written on 10 February:

One of my NCO’s is off on leave today, so I’m sending you 2 snapshots by him, taken by Eric Long, our doctor,33 in the trenches on Christmas Day. We mayn’t send photos home in letters, so I seize this opportunity.

Wilson is the English International Rugby Player, he looks like a girl in the photo, but he doesn’t really.34 My beard was just beginning to grow, so I look a dirty beast. You see the way I wear Katie’s35 cap.

… My dugout is just behind me, in the photo.

Buchanan-Dunlop sent further news of the continuing truce in a letter to his wife on 27 December:

Last night turned very wet and unpleasant. I was on watch in the trenches from 8 pm until 4 am, with one hour off. I felt uneasy in my mind about our “friends” opposite. The mud was awful, “knee deep” doesn’t look formidable when written down, but in reality it’s pretty bad. My subaltern, six feet high, stuck so fast that he had to be pulled out by his men. You can’t compete with it. Today it has rained a good deal & the mud is a bit worse. I’m engaged in great engineering works. A large pond has appeared in the centre of our trenches which we drink from. So “it’s an ill wind”. I’m extremely well, & inventing jokes to fire at the men when it’s wetter than they like, & they get a bit downhearted. Bullseyes, I find, cheer the sentries up at night. Talking about bullseyes, a glorious box came today from the Junior A & N stores – Mother I presume – please thank her awfully. A cake, candles, raisins, almonds, preserved fruits etc and a large tin of marmalade which I must keep till we get out of the trenches.…

Such a curious situation has arisen on our left. The Saxons all today have been out of their trenches & had tea with our men halfway between the trenches. They only fire four shots a day. Two of their officers and 70 men came into our trenches, & have refused to return. Our men were rather non-plussed, as owing to the friendly relations between the two parties they couldn’t [very] well take them prisoners, & yet they insist on staying. Poor fellows, the Saxons quite like us, & hate the Prussians, & I believe their trenches are much worse than ours. Herbison, one of our subalterns,36 who speaks German, exchanged cigarette cases with the German commandant.37

Interestingly, none of this is mentioned explicitly in 1 Leicesters’ war diary, which simply states:

24 [Dec.] Snow. Quiet all day.

25 [Dec.] Frost. 2 men killed one wounded.

26 Dec. Frost Quiet all day

27 [Dec.] Thaw & rain, trenches very wet & parapet falling in.38

There are no more references in Buchanan-Dunlop’s correspondence after this to ceasefires or truces involving 1 Leicesters taking place, although he does mention, in a letter to Mary of 28 December, a Saxon cap-badge which may well have been given to him during the truce, as the regiment from which it came was one of the Saxon regiments to his left:

I’m writing to you with Robert’s pencil – a present which I wanted very much, & am delighted to have. Please thank him very much. I’ve got him a badge out of a Saxon soldier’s cap. I’ll try and get it home to him.

And again to his wife, on 30 December:

I got your dear letter today sending one from Robert, please thank him very much & give him the enclosed – a badge from the cap of a soldier of the 107th Saxon Regt —.

The 107th Saxon Regiment were particularly committed to the truce, refusing to fight when ordered to do so on Boxing Day; they also held truces with 3rd Battalion The Rifle Brigade, The Queen’s Westminster Rifles, and 1st Battalion The North Staffordshire Regiment.39 Meetings between the troops seem to have been over by 28 December. Buchanan-Dunlop and his company finally left the line, after 24 days, on 2 January 1915, going into billets in Armentières.40 However, even from behind the lines he was able to report that an informal truce still continued at the front, writing to Mary on 10 January 1915:

The Saxons still refuse to fight the Regiment opposite to them,41 it is a funny game. They say “We are Saxons, you are Anglo-Saxons, why should we fight”?

– a claim (‘they are really the same as the English by race’) repeated in Private Potterton’s account; whilst the same phrase, about Saxons and Anglo-Saxons, was used on Boxing Day 1914 by an officer of the 107th Saxon Regiment when warning C Company of 1st Battalion The North Staffordshire Regiment that hostilities were about to resume.42

That evening, Buchanan-Dunlop had first-hand experience of the continuing cessation of hostilities, writing to his wife the following day:

I and my Company paraded at 8.15 pm & returned at 3. am, having been marching and digging all the time. The enemy, 50 yards away, turned their searchlight on us, but never fired a single shot, altho’ we were working in the open. They were the Saxons, who have been at peace since Christmas. There seems to be a feeling prevalent that the war won’t last very much longer. I don’t know, myself.

The Saxons still seemed to be holding to a ceasefire on 13 January, when Buchanan-Dunlop wrote to his wife:

I have to go into the trenches again on Saturday (today’s Thursday) & only stay in for a week at a time. We shall be opposite the peace-loving Saxons. Last night they shelled (not the Saxons) the trenches we were in last, but apparently without much effect.

It looks as though the presence of the Saxons, and perhaps their unwillingness to fight, were regarded as sensitive information. Following a meeting with Brigadier-General Ingouville-Williams on 15 January (on which more below), Buchanan-Dunlop wrote to Mary the same day that:

We are not, when in our new trenches, to mention the Saxons in our letters home, so you will hear nothing about them in future.

Buchanan-Dunlop and his company returned to the line, in new trenches at Rue du Bois, on 16 January, and were withdrawn to Armentières only four days later on the 20th, the result of a new pattern of deployment implemented by the divisional commander, Ingouville-Williams.43 Whether Saxons or not, the Germans opposite Buchanan-Dunlop were still willing to express their resentment at being shelled on 20 January. Buchanan-Dunlop wrote to his wife the next day:

Although, in our trenches we are too near the enemy for either lot of fire-trenches to be shelled; yet our artillery yesterday shelled a factory a little way in rear of the German lines. Our vis à vis told us (shouted across) more in sorrow than in anger that they had had 16 killed & wounded by it; the exact number that a Regt just behind us lost the day before, from German fire.

And on 27 January there was heavy fire coming from the German artillery. Buchanan-Dunlop wrote to Mary that day:

The Kaiser’s birthday today & our vis à vis have flags flying. The Germans are firing hard over our heads with heavy guns at one of the Armentières Churches, the one I’ve sent you a photo of. It’s about all they can do to celebrate the occasion, as they tried to find our guns which “saluted the happy morn”, but couldn’t.

And the truce had certainly come to an end by 3 February 1915, when Buchanan-Dunlop wrote to Mary:

Just a little note before I go off to the trenches.… The long truce between the Saxons & ourselves is broken, and there is brisk fighting here now. As the enemy is so close, one has to be very careful. We have never been into these trenches under these conditions before; so I’ve been detailed to go down “in daylight” & inspect them before the Battalion arrives. I’ll be very cautious going down there.44

So, from Buchanan-Dunlop’s letters we know that he and a group of officers and men had sung carols, presumably from within their trenches, to the Germans on Christmas Eve; the Germans had replied in kind. On Christmas Day, the two sides met for an hour in no man’s land and exchanged tobacco and newspapers; this seems, if it was instigated by anyone, to have been started by the Germans, who drew the line down the middle of no man’s land. According to Buchanan-Dunlop, the General had been angry at the informal truce, but appeared to have been mollified by the service for his company held by Buchanan-Dunlop.

Looking at letters describing the same events written by other soldiers of the Leicestershire Regiment (see Appendix 1), it becomes clear that experiences varied from company to company, and even from soldier to soldier. Nevertheless, Buchanan-Dunlop’s account largely tallies with those of other soldiers. As we might expect, the atrocious weather leading up to Christmas features in many letters, from Private Slater, Lance-Corporal Howard, an anonymous corporal, Corporal Dalby, Private Clibbery, Private Parker, and Sergeant Hayball; Lance-Corporal Howard, the anonymous corporal, and Sergeant Hayball also describe the frost on Christmas Day.45

Private Cooper, Lance-Corporal Morris, Private Slater, and Sergeant Hayball all tell of the Germans singing to the English, and vice versa, on Christmas Eve. Sergeant Hayball states that the Germans started singing first, with A Company (not Buchanan-Dunlop’s C Company) replying first, Private Parker only mentions the Germans singing, Private Slater mentions only secular songs, and Corporal Dalby says that the British sang carols ‘in which the Germans took part’.

On Christmas Day, Lance-Corporal Howard, the anonymous corporal, Private Lowe, and Private Clibbery all describe the two sides meeting in no-man’s-land, midway between the two lines – although Lance-Corporal Howard says that the two sides were actually in each other’s trenches ‘further along the line’, and Lance-Corporal Morris writes ‘they are visiting each other’s trenches’, implying that this happened amongst the Leicesters, too; this echoes Buchanan-Dunlop’s description of Saxon visits to British trenches on 27 December. Like Buchanan-Dunlop, Private Harding mentions the exchange of newspapers; Privates Cooper, Slater, Clibbery, and Private Harding, the exchange of cigars and/or cigarettes (Lance-Corporal Morris refers only to tobacco); and, whilst non-one else exchanged cap badges, Private Cooper talks of buttons being given, and Private Parker of the swapping of souvenirs. Other items exchanged, not mentioned by Buchanan-Dunlop, were money (Private Slater), bully beef (an anonymous soldier), and jam (the same soldier, and Private Harding). Events not described by Buchanan-Dunlop include burying the dead (the anonymous corporal) and improving the trenches (Sergeant Hayball, contradicting Buchanan-Dunlop’s account of warning shots being fired when the Leicesters attempted repairs). Buchanan-Dunlop’s uneasiness about the Germans’ intentions, described in his letter of 27 December, was shared by the Leicesters’ Commanding Officer, Colonel Croker, according to Sergeant Hayball, and also by Private Cooper.

Accounts vary as to precisely how the truce started. Buchanan-Dunlop says that the Germans drew a line halfway between the trenches. Private Cooper says that a British suggestion to stop shooting was met by a German invitation to visit; Lance-Corporal Howard writes that the Germans requested that shooting stop, but that a meeting was instigated by the British, via a sign drawn up by ‘one of our officers’. According to Sergeant Hayball, B Company were the first to get out of their trenches on the British side, only to see the Germans doing likewise. Only Private Brown, interviewed 67 years after events, mentions Buchanan-Dunlop taking a leading role, and that only in the singing. It’s difficult to know what to make of Private Parker‘s claim that ‘our second in command went into their trenches’. Buchanan-Dunlop, who was second-in-command of the battalion, makes no mention of it; Private Parker’s letter was published only in late February, so might have been written some time after events; and precisely whose second-in-command he means is unclear: platoon, company, or battalion?

The truce had continued over Boxing Day on Buchanan-Dunlop’s left, but not directly opposite him. Although Corporal Dalby agrees that the Prussians started shooting again on Boxing Day, he is contradicted by Lance-Corporal Howard and Sergeant Hayball. Despite Buchanan-Dunlop’s worries about the aggressive Prussians in front of him, the truce continued into 27 December, with both sides sharing tea in no man’s land, and a group of German officers and men unilaterally coming over en masse into the Leicesters’ trenches and refusing to leave – a claim repeated by Lance-Corporal Howard. The Saxons’ dissatisfaction with the war is a common theme in reports of the truce, and appears in the accounts of Private Cooper, the anonymous corporal, Corporal Dalby, Private Newby, and Private Potterton. Privates Harding and Potterton both described repairs being made to the Leicesters’ trenches – as does Buchanan-Dunlop.

Meetings between the troops seem to have been over by 28 December; an unofficial ceasefire persisted until at least 11 January 1915, even longer on the part of the Saxon infantry, but not the German artillery: Buchanan-Dunlop mentions it continuing until 13 January, Corporal Dalby until at least the 14th; serious hostilities with all German units had resumed by 3 February. The accounts of Privates Newby, Harding, Potterton and the anonymous soldier, all published only in February 1915, also suggest that the ceasefire continued well into January.

Accounts in the press

Brown and Seaton describe the extent to which the truce seized the imagination of the British press, with letters and articles on the subject appearing in many papers from the end of December onwards.46 A few of them drew upon letters written by Buchanan-Dunlop, and mentioned him by name.

The Scotsman on 4 January 1915 contained news from a letter written by Buchanan-Dunlop on Christmas Day to one George Davidson, which seems to have had very similar contents to the one above written to his wife. This was combined with news of a sermon preached by the headmaster of Loretto’s preparatory school, the Rev. G. N. Price, on 3 January, which also spoke of the Christmas truce:

Loretto School carol programme sung between hostile trenches

Major A. H. Buchanan-Dunlop, second in command of the 1st Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment, an old Loretto boy, who is a member of Loretto School staff, and was called up for war service as one of the Reserve of Officers, has written a letter from the trenches, dated Christmas Day, in which he describes how, by mutual agreement, there was a cessation of firing; how British and Germans met half-way between the opposing trenches to exchange cigarettes and chocolates; and how, from the programme of the Loretto School concert given at the close of the term, December 17th, which had been sent out to him, he and some brother officers and soldiers sang the Christmas carols printed thereon, also some Christmas hymns, to which the Germans replied with some of their sacred songs.

Preaching in St Paul’s Episcopal Church, Edinburgh, yesterday, the Rev. G. Nowell Price, of Loretto, in referring to this, said: — During the past few days you may have read in your papers, or in letters that have actually come from the trenches, as I have done, of the marvel of the Christmas Day just past – how in many parts of the firing line there was, by mutual consent, a truce of God; how friend and foe met to exchange some small luxury; how they sang one to another the old Christmas carols and hymns. “I shall never think so badly of the Germans again,” writes one. “I had no idea they were such decent fellows,” is the homely phrase of another. Is it merely fanciful to say that, on that anniversary of the birth of God’s Son, there must have been some gracious influence of the spirit of Christ brooding over the combatants and suggesting, though but for a brief moment, the brotherhood of man in the great family of the Father?47

We know what the hymns were thanks to an article in the Daily Mail of 4 January 1915:

Carols in the Trenches

A major of the Leicester Regiment with his brother officers and soldiers sang carols on Christmas Day to the Germans who replied with sacred songs. The major and his men sang:

- Come let us all sweet carols sing (Champreys)

- Good Christian Men Rejoice (Traditional)

- The Manger Throne (Steggall)

- Sleep, Holy Babe (Dykes)

- See Amid the Winter Snow (Goss)

- Good King Wenceslas (Helmore’s collection)48

The numbers comprised the first part of the programme of a Christmas term breaking-up concert given on December 17 in the famous Scottish School, Loretto. The programme had been sent out to the major who is an old boy of the School.49

But most significant was the front page story in the Daily Sketch of 5 January. Under the headline ‘Major who sang carols between the trenches’, the Sketch published a photograph of Buchanan-Dunlop, captioned ‘Major Buchanan-Dunlop, the leading “chorister.”’ To the right was a picture of Germans singing in their trenches, captioned ‘The Germans’ melodeon-player accompanied the singers.’ Below were

Photographs of British and German trenches. The ground between them is known as “No Man’s Land,” and it was there where the rival armies met to sing peaceful carols. Major A. H. Buchanan-Dunlop, second in command of the 1st Leicesters, was one of the moving spirits in the wonderful Christmas truce, when British and German soldiers met between the trenches, and sang carols of peace. Major A. H. Buchanan-Dunlop is an old boy of Loretto – the famous Scottish school – and the programme of carols sung on December 17 at his old school was sent out to him. It was from this programme the major chose the carols he sang to the Germans.50

Consequences

The framed copy of the Daily Sketch‘s front page story which is preserved at Loretto has below it a manuscript note:

The significance of this page of the Daily Sketch is already known to those who heard Colonel Buchanan Dunlop Toc H. tell the story of the Christmas Truce to a gathering at Mark I on Dec. 22nd. 1920. The faked picture on the right was the means of inflicting a great injustice on a gallant & much loved man.

A. H. B.-D. was one of the first supporters of the House in Pop., being at that time commanding the 1st Leicesters in VI. Division.

P.B.C.

P.B.C. is presumably the Reverend Phillip Byard Clayton, known as Tubby, who founded Talbot House, a rest house for soldiers of all ranks in Poperinge (‘Pop.’) in 1915, which became known as Toc H, using the phonetic alphabet of the time. Mark I is the second of Toc H’s hostels in London, in Queensgate Gardens, Knightsbridge, established in 1919. As Clayton notes, Buchanan-Dunlop was an early supporter of Toc H, which went on to become a significant charity and voluntary movement focussing on fellowship and service.

This aggressive response suggests that the Sketch article was not as neutral as it at first appears. In fact, it subtly played up Buchanan-Dunlop’s role in ‘organising’ a truce, calling him the ‘leading “chorister”’ and a ‘moving spirit’, as well as claiming that the Germans had accompanied the Leicesters’ carol-singing, rather than replying to it. And the inclusion of a large portrait of him on its front page would only have increased the impression that he was in some way responsible for the truce.

As Clayton’s later note suggests, the inflated role given to Buchanan-Dunlop in the Sketch had unfortunate consequences. Buchanan-Dunlop wrote to Mary from billets in Armentières on 6 January 1915:

Darling girlie, the General51 is on leave in England, but comes back on Friday. I’m rather frightened of what he’ll say when he does come. He is upset at the informal truce on Christmas Day, and now – my photo is in the Daily Sketch as “one of the leaders in arranging the Christmas Truce” – It isn’t true of course, but there it is, it was another regiment that arranged it, but he won’t think so. For myself I don’t much mind what anyone says, but I don’t want the General to be snuffy to the Colonel52 about it. Who sent the photo? One has to be awfully careful. I’ve already had Major S. S.53 round here, talking about the piece in the Daily Mail. If no names, nor Regiments were mentioned, it wouldn’t matter a bit. I shall now be known as “the leading chorister” – luckily I’ve grown a beard so no one will recognize me. Well, it’s done now, & can’t be helped.54

Matters escalated, and the next day (7 January), Buchanan-Dunlop wrote to his wife:

This morning, as I thought, I had a memo from the Colonel requesting a full explanation of that photo & account, in the Daily Sketch, of the Christmas carols. Apparently Army Headquarters are moving in the matter. It’s rather a nuisance altogether, however I shall doubtless survive it.55

Letters which Buchanan-Dunlop received on 8 January seem to have established how his photograph and news of the carols and truce reached the press via the Loretto prep school headmaster G. N. Price (‘G.N.P.’); Buchanan-Dunlop wrote to his wife on 9 January:

Last night I got letters from any number of folk as I think I told you in yesterday’s letter & four copies of the Daily Sketch, underlined and blue-pencilled. Sir H. Smith Dorrien56 is awfully angry about it. Luckily Price’s letter came after I had had to give my official explanation, in which I truthfully said I hadn’t any idea of how it got there – for young Brown57 told me that Father knew nothing of the photo, as he had discussed it with him. G.N.P. referred to my letter in his sermon in Canon Reid’s church, & an account of his sermon was in the Scotsman, as also extracts from my letter to George Davidson – Little McGill, the fat reporter, is of course the real culprit, he went & got my letter from Davidson, & borrowed from G.N.P. the photo you gave him of me. G.N.P. is now rather frightened at what has happened & hopes I’m not “awfully sick about it”. I shan’t tell him what a horrid nuisance it has been. The Brigadier General58 came hurrying to our Headquarters to investigate directly he heard about it. However as I say I’ve no military career to blast, for I certainly shouldn’t dream of staying in the service if Sconnie59 wants me back, & I can get to Loretto again – Also I don’t mind generals, and am not at all afraid of them.

… [later, at 8 o’clock] Your letter of the 5th just came, also letters from Uncle P. muncle, [?] & G.N.P.

Poor old Price sent my photo to the paper, which has caused all this fuss out here – please don’t mention the fuss to him, he means so kindly.60

The matter continued to drag on. Buchanan-Dunlop wrote of it again to his wife on 11 January, after a night spent digging trenches (see above):

The General is pleased with our work last night. He is still worrying over that wretched Daily Sketch, & the whole correspondence came back last night for further explanations from me. Bother the whole thing!

The affair continued to exercise the Staff, and Buchanan-Dunlop. He wrote to Mary at length on 13 January:

I’m much annoyed at the course events in connection with the “Daily Sketch” atrocity are taking. Today, the General wrote to the Colonel asking him “to convey to Major Buchanan-Dunlop his great displeasure at this officer’s disobedience of orders” – I immediately wrote back to the Colonel and said “I have never before in my service been indicted for disobedience of orders. I would respectfully urge that I did not disobey orders in the present instance. I would also respectfully request that I may be allowed to to see the Brigadier General on this matter” – I am insisting on seeing the General personally, as I am going to try & make him retract what he has said about “disobedience”. I did not disobey any order. There’s no order against singing anything in our own trenches. There’s no order against visiting the Regiments on our left & right and if, as in this case, when I visited one on Christmas Day I found them out of their trenches & a lot of Germans with them, I cannot be held responsible for the state of affairs.61

I have carefully kept a copy of the General’s orders sent round on Christmas Eve – there’s only one I did not obey, and I at once at the time wrote to the Colonel giving him my reasons for not complying with it, which were most significant military ones, and he wrote back “I approve”. Further even if the General still insists that I disobeyed orders, I can point to the fact that on Christmas Day, when he visited my trenches, I had a long talk with him & told him of everything I had done – He ought then & there, if he considered I had done anything wrong, to have written at once to the Colonel, & said so. It’s not as if he had heard of it just now for the first time. — No it’s just that he’s annoyed at seeing his beloved Brigade practically ridiculed in the cheap press, and he’s determined to “take it out” of somebody.

I’m quite determined though, that I won’t take it “lying down” The Colonel is absolutely with me, & has authorized me to tell the General that he is perfectly satisfied with my conduct throughout; & he agrees with me that if the Brigadier doesn’t give me satisfaction, I should refer the case to the Divisional General. Possibly I shall be shipped off home as a nuisance, but I mean to fight it out – Its [sic] a true instance of “Save me from my friends”. I know all this will interest you my darling, so I write at length on the subject. You needn’t be in the least bit worried, I’m quite capable of keeping “my end up”; & I have no military career to “blast” so I’m in a very strong position.

… The rest of the morning I spent with the Colonel discussing the General’s letter.62

Buchanan-Dunlop was also marshalling his evidence, as we see in a letter to his wife of 14 January:

Thanks my darling for the extract from my letter. It will be most useful if the General asks me exactly what I said. I have heard nothing further from him yet.

… My girlie, you’re not to worry any more about the “Daily Sketch” & the other papers. It was G.N.P. of course who gave the photo.

Buchanan-Dunlop finally met Ingouville-Williams behind the lines on 15 January, writing to Mary with an account the same day:

I also saw the General, re his accusation of disobedience, he still sticks to it that I disobeyed the spirit, if not the letter of his orders for Christmas Day; He was not the least bit affable, quite the reverse. I said all I had to say, but I only got a wigging for my pains. So there I think we’ll let the incident close. He rather conveniently forgot that I had told him all about it on Christmas Day, & that he had said nothing then.63

Whilst Ingouville-Williams continued to disapprove of Buchanan-Dunlop’s behaviour on Christmas Day, he was not unappreciative of his work as a company commander. Buchanan-Dunlop wrote to Mary on 21 January:

I did a lot of work in the trenches64 with my company & earned the General’s outspoken [?] approval. Col. C65 says I’ve secred [sic; secured] a very big good mark, all I can say is that, with this General (Ingouville-Williams) I shall want it, after the Daily Sketch episode. However, after all, the approbation of the military authorities, altho’ nice to have, is not essential to me now as it was when I was a subaltern.

The matter finally seems to have been resolved – at least to some extent – on 22 January. As Buchanan-Dunlop wrote to his wife that day:

To refer back to the “Daily Sketch” incident, for, I hope, the last time — General Williams said I had disobeyed his orders in the spirit if not the letter. — He sent me down orders on Christmas Eve that the sentries were to be extra vigilant; & he maintains that by leaving my trenches & going to the Saxons, I broke the spirit of his order as I couldn’t there possibly see that my sentries were vigilant. It was of course difficult to explain to him, & sounded like quibbling, to say that the N.C.O’s on duty were responsible that the sentries were vigilant, that my Captain & subalterns were in the trenches on duty all the time; that if I couldn’t trust them all to see my orders carried out without nosing around myself, what’s the good of any of them; that in the ordinary course of events I left my trenches every day to visit Headquarters; that in the day-light any signs of an attack would be so obvious that I could have been back, & the attack repulsed, almost at once – that at night when sentries always had to be alert I never dreamt of leaving my trenches – and that on Christmas Day the enemy never fired a shot till dark. Consequently I had no idea that by leaving my trenches for an hour I could possibly be disobeying his orders. — No, he took a most obstinate & decided view of the incident, & stuck to it that there was disobedience. (Practically every officer except my Captain and subalterns; & Col Croker was there on Christmas Day with me.)

I thought matters over for a couple of days, & concluded that he had probably done the same – so when I met him alone one morning in the trenches, I began to talk to him about it – he said the incident was closed, & he didn’t want to hear anything more about it; but I stuck to my guns & said, I regretted extremely that I had given him occasion to think that I had disobeyed his orders, but that I had been genuinely astonished when I heard he considered I had done so; but that I saw his point of view as well as my own. He said that I had now to “redeem my character”.

I quite like the man really, but he is odd, altho’ a good soldier. I felt that I had better express regret, & not stick out for my side of the question; as it’s so much better to be on a pleasant footing with everyone. I fancy he was pleased at it. The whole incident was the more unfortunate as the Colonel had just asked the General to recommend my being made a Major in the Regiment, as well as in the Territorials; & of course he wouldn’t whilst this was on. However Col Croker says I have pleased the General by my work in the trenches, & he thinks that all is now as it was before; & he’s going to see him tomorrow about forwarding this recommendation to Army Headquarters, which would mean my getting it all right. Col. C says my being in the Army List at the bottom of the list of Captains means nothing, as there’s no date opposite my name; & anyway as a Territorial Major I rank senior to all Regular Captains; but junior to all Regular Majors. As a Reserve Major, I should be senior to all Special Reserve & Territorial Majors. — There my sweetheart now you know all about it.66

But by now, Buchanan-Dunlop clearly had a reputation amongst the Staff. He wrote to Mary on 23 January:

A day or two ago a general staff officer from Army Headquarters came down with the general to see our trenches.67 I was showing the latter a barricade I had made & the former said to our Colonel “Who is that officer”? When the Col. told him, he said, “Oh, the notorious Major B-D” & with that he screwed an eyeglass into his eye & had a good look at me. This the C.O. told me. He was an Indian Cavalry officer, so what could he know about trenches?68

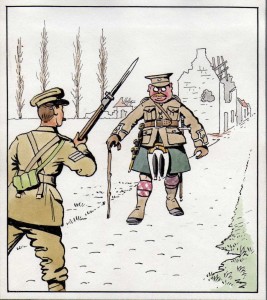

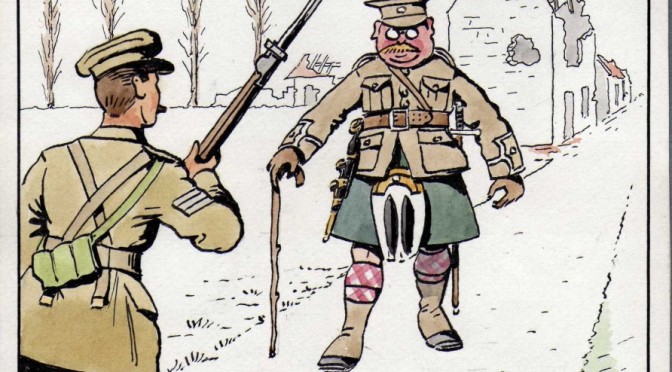

I suspect that that staff officer from the Indian Cavalry may have inspired one of the drawings in Buchanan-Dunlop’s Alphabet from the Trenches.

By 26 January, when Buchanan-Dunlop wrote to his wife, Ingouville-Williams seems to have been well-enough disposed towards him:

Not much news for you today, my darling, I’ve been hard at work all day & got through some satisfactory jobs.69 The General was pleased when he came round this afternoon.

And Buchanan-Dunlop clearly felt that the events of Christmas Day 1914 would continue to follow him, writing to Mary on 29 January:

Violet70 does seem to think G.N.P. has erred deeply. I don’t mind a bit darling, & he must never know the little worry I had over the business. Capt. Holmes71 wrote to me today enclosing THE picture from the Daily Sketch. It fails to “dread” me now – not that he meant it for anything but most friendly – shall we say – approbation, not the Press notice, but the carolling. I shall never escape from it.

And he still felt he was not fully redeemed in the eyes of the Staff two days later, when he wrote to his wife:

I’ve heard nothing further about my application. I haven’t worried about asking at Brigade Headquarters as I’m not yet in good odour.

Aftermath

Brown and Seaton record a family tradition that his involvement in the truce later cost Buchanan-Dunlop the award of a DSO.72 But he was well-enough regarded to have again been appointed Second-in-Command of the battalion by his Commanding Officer, and as temporary Commanding Officer by Ingouville-Williams, in February 1915. He wrote to Mary on 5 February:

Sweetheart I’m actually 2nd in command now & living at Regimental Headquarters. I’ve handed over my company to Capt Wilson.

… Colonel Croker is very seedy I’m sorry to say. Last night he was too ill to do anything & the General put me in command of the Regiment.

And he was sufficiently well-regarded by the Staff to be given the command of his Battalion on 25 October 1915, after Lieutenant-Colonel Stoney Smith, then in command, was killed by a sniper. He was promoted temporarily to Lieutenant-Colonel,73 and held the post until 6 February 1916.

That year, he was evacuated to England as a casualty, and invalided out of the army the following year due to the effects of gas. He returned to Loretto, and joined the Volunteer Corps, commanding 3rd Battalion The Royal Scots (apparently also known as the Midlothian Volunteer Battalion) until 1918.

After the war, he continued to command the Loretto OTC until 1928, when he became Bursar of the school, a position he held until his retirement in 1937. Two years later, when war broke out again, he joined the Edinburgh Air Raid Precautions (ARP) service, and commanded a company of the Home Guard. In 1945 he received an OBE for his wartime work as County Army Welfare Officer for the City of Edinburgh. He died on 13 December 1947, aged 73. His biography on the Leicesters’ website notes that, having earned the Defence Medal for his service in the Second World War, he was entitled to wear medals for service in three wars.74

His service record and his decorations show that Buchanan-Dunlop was a conscientious and long-serving soldier with a strong sense of duty – and perhaps a slightly sceptical attitude to his superior officers, which he would have shared with soldiers throughout the ages.

Like many of the soldiers on the Western Front during the Christmas of 1914, Buchanan-Dunlop certainly participated willingly in the truce; but the notion that he was in some way a leading light in the affair seems largely to have been due to an excitable report in the tabloid press. The Daily Sketch report, in particular, caused Buchanan-Dunlop a great deal of trouble with his superiors, and he was convinced that it misrepresented his role. But even then, he could see a positive side to the affair, writing to his wife on 14 February 1915:

Just got your dear letter written on the 11th. Well, if Loretto benefits in any way from the “Daily Sketch” affair I shall be quite satisfied with everything. People are so funny in their ways of looking at things though.

According to Clayton’s inscription beneath Loretto’s framed copy of the Daily Sketch’s front page, Buchanan-Dunlop continued to believe that reports that portrayed him as some kind of ‘moving spirit’ were incorrect, and did him a serious disservice. Taking his view (and after all, he was there, between the lines, 100 years ago), we should therefore be wary of accounts which state that he led the truce in any way. And if we downplay his role, as he would have wished, we do not in any way downplay the significance of the events in which he was involved. The Christmas truce remains a remarkable occurrence, even after some of the surrounding mythology has been stripped away.

Appendix 1: further accounts of the Leicesters’ truce

Mike Hill has very kindly provided me with copies of all the published accounts of the truce by soldiers of the The Leicestershire Regiment that he has been able to find (including several that he was unable to include in his book, Christmas Truce: By the Men Who Took Part: Letters from the 1914 Ceasefire on the Western Front (n.p.: Fonthill, 2021), ISBN 978 1 78155 812 6), as well as the original sources and dates of publication. Rather than insert them into the narrative above, I’ve included them here. For completeness’ sake, I’ve also included Sergeant Hayball’s account, published in Wylly’s regimental history, and Private Brown’s much later account; these were originally given in the main text, above.

The letters are arranged – as far as it can be deduced from publication dates – in the order in which they were written. Generally, it looks as though it took about eight or nine days after a letter was written before it found its way into the newspapers.

Private F. Cooper

1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

On Christmas Eve the distance between our trenches and the German trenches was 200 yards. The enemy had lighted up their trenches with Christmas lanterns, and both sides were singing carols. One of our fellow shouted to them, ‘Why the —- don’t you take a tip, and chuck it,’ and they shouted back, ‘come over to see us.’ Presently both sides were out of their trenches, shaking hands and exchanging tobacco for cigarettes and chocolate. Four of us went over and were met by six Germans, in front of their trenches.

They gave us cigarettes, and buttons off their jackets as souvenirs. There was not a shot fired from 6:30pm on the 24th till midnight on the 26th. This was not an official armistice, but an understanding between the two parties concerned. On our right and left guns were playing – – – – with the enemy. The Germans who met us were mere schoolboys. To tell you the truth, I would have a scrap with six of them. Their officers told them the war will be over in three weeks; in fact they wished the whole show was over. These fellows are not to be trusted, and we think there is something behind the supposed friendship.

Leicester Daily Post, 2 January 1915.75

Lance-Corporal S. Morris

1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

Things are very quiet here today (Christmas Day). The Germans have asked us not to shoot, and they offer to do the same. The men got quite friendly, singing songs alternately, and exchanging tobacco – in fact, they are visiting each other’s trenches. But what’s in store for tomorrow?

Leicester Chronicle, 2 January 1915.

Private A. Slater

1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

I didn’t get a change of clothing or a wash for 24 days, and everything I possess now is wet through. Under the circumstances I didn’t enjoy my Christmas but the Germans did in front of us, for they were shouting and singing in some parts of the trenches. Some of our chaps exchanged fags and money with them, but it doesn’t do to be too chummy with them at these times.

Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 11 January 1915.76

We had the order come down our trenches that we could sing, and of course I, with the rest of my platoon, started. When I got a chance to sing my song ‘Just for tonight,’ I let it go. After that I gave them ‘Sunshine from morning till night,’ and the Germans gave us three cheers! It wasn’t bad, was it?

Lance-Corporal J. Howard

The Leicestershire Regiment

We spent a merry Christmas in the trenches, up to our knees in water. You perhaps do not realise that this is true, but I can vouch for it. It has been really raining now for about a month, and is still raining, and without drains, the extra amount of water cannot soak into the ground. A great deal, therefore, stops on the top, much to our discomfort. We work hour after hour trying to keep it down to the knee limit, but it beats me at times.

Christmas morning dawned with a beautiful frost, and no shooting by the enemy, a thing which surprised us, considering the Germans hardly ever missed firing a volley or two before breakfast, to let us know that they still occupied the same ground. So our fellows accepted the request not to fire.

This, however, was not quite good enough for Christmas Day so we decided to ask the Germans to have a chat, smoke and drink. To do this we drew up a little scheme, and one of our officers stuck up a board, on which was written an invitation. The Germans came out of their trenches and exchanged greetings of a very cordial nature on the halfway line.

We spent some time in swapping names and addresses and small tokens as souvenirs. Further along the line the Germans entered the English trenches and vice versa, partaking of drink and food together. When Christmas Day was over the fighting continued as usual.

Burton Observer and Chronicle, 14 January 1915.77

Corporal

1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

Since my last letter we have had a good spell in the trenches – 22 days of it. Rain every day almost – mud and water up to the knees. Christmas Day was of the season – clear, frosty air. Our troops and the enemy in front – a Saxon regiment – met on friendly terms between the trenches, and spent part of the day burying the dead. Many of the Saxons said they were sick of the war and longed for its end. I am sending you a parcel of curios which will interest you.

Leicester Evening Mail, 18 January 1915.

Private J. Lowe

D Company, 1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

The Germans were quite friends with us on those days two days. They left their trenches and came over to our officers and shook hands with them as they came along the railway line, but we did not allow them in our trenches. It seemed a shame to start fighting them again.

Leicester Evening Mail, 20 January 1915.

Corporal William ‘Bill’ Dalby

1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

We have been in the trenches for 22 days, including Christmas and New Year’s Day. The weather has been so bad that we had to evacuate the trenches and build a barricade on the ground level.

It was up to the knees in mud and water for 19 days. Then we had three days’ rain which made it almost shoulder deep.

We had an unofficial truce on Christmas Eve. In that time we had a ‘leg stretch’ and sang carols, in which the Germans took part.

On Christmas Day we found that we had before us the Prussian Guard and to our left front the 107th Saxon Regiment. The difference between these two was that the Prussians only had a truce for 12 hours, whereas the Saxons have not fired a shot up till the time of writing (January 14).

I got into conversation with one of them and he told me that they ought to be fighting for Belgium instead of against her. This was the regiment that wore the photos of the King and Queen of the Belgians when in Antwerp. He also said that if they could get the official news that Austria was having peace the whole Saxon race would surrender.

He said he was married and had a good business in London. He would be glad to get back there.

Leicester Evening Mail, 23 January 1915.

Private A. Newby

1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

We got relieved after being in the trenches 23 days. Then we had 14 days’ rest, and then went into the trenches further on the left, and when we got there the enemy was not firing at all. Their trenches were about 50 yards from ours. This race of Germans are the Saxons, and they hold about 10 miles of trenches, and none of them have fired a shot since Christmas. The Saxons consist of about 300,000, and they have told us that they are a beaten team and would like to see the end of it as soon as possible. They tell us that about half of them come from England, and they say they are waiting to see if Roumania is going to start, and if so they are going to chuck it in.

Leicester Chronicle, 30 January 1915.78

Private Alfred Harding

1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

We have gone back to the trenches now, and it is a sight. The North Staffords named it Dead Man’s Alley, graves everywhere. If you dig a spit or two you dig some poor chap up—I did the other day. But there are a decent lot of fellows in front of us now—Saxons, they don’t like the Prussian Guards. They haven’t fired a shot since the day before Christmas nor have we. I believe they will surrender. Our trenches are only 80 yards and we meet each other halfway. We give them tins of jam for cigars. It seems strange but it is true.

Bedfordshire Times and Independent, 5 February 1915.

Private H. Potterton

1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

The surroundings here are most extraordinary. A portion of the German line is occupied by Saxons, who have never fired a shot since Christmas Eve. They emphatically declare that they are really the same as the English by race, and that they are determined not to fire another shot, and as soon as the British start to advance in Flanders they’re ready to surrender.

Owing to the incessant rain, the trenches became flowing streams, and, of course, had to be evacuated, each having to build a parapet of sandbags and loose earth to take the place of the trench. As soon as daylight appears each day the Germans can be seen all over the place as busy as bees, carrying planks, digging, pumping water out of the trenches, and doing a hundred and one other jobs; and the British troops are just the same – and not a shot can be heard.

Westminster Gazette, 6 February 1915.79

Private Ben Clibbery

1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

I suppose you have seen in the papers about the truce on Christmas Day. It was rather funny to be talking to the men we had before been trying to kill, and it was quite nice to get out of the trenches to stretch our legs in the daytime. We had been in a fortnight on Christmas Day, and they (the Germans) had been pretty busy all the time. When we went over to them we took plenty of cigarettes which we exchanged for tobacco and cigars. They seemed to be quite good chaps so different to what you would think they were. We stayed in those trenches 22 days and I can tell you it was pretty bad as we were up to the knees in water by the time we went out. But still, it is no use troubling about small things like that.

Leicester Evening Mail, 16 February 1915.

Private John Andrew Parker

1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

We were 22 days in the trenches, including Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. It was the worst time I have ever experienced; we were up to the knees in slush and water. We had a truce with the Germans on Christmas Day, and our second in command went into their trenches. The enemy indulged in the singing of carols. They were Saxons, and there was a great deal of handshaking and exchanging of souvenirs by the opposing forces. Their trenches were only 70 yards away. The Saxons were relieved by the Prussian Guards, and of course the fun commenced with their arrival.

Belfast News Letter, 19 February 1915.80

Soldier

1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

There is not much fighting where we are at present. The enemy are only 60 yards in front of us. They are the Saxons and they hold a truce with us. They promised, if we do not fire at them, they would not fire at us, and there has not been a shot fired between us since Christmas.

They seem a decent lot of men, and most of them can speak English. We walk on the top and in front of the trenches, and so do they. When we go digging in front of our trenches during the day we are so near the Saxons that we generally have a chat together. If we have a tin of bully beef or a jam to spare we throw them over to them, and they throw us cigars in return.

One of our fellows took a paper over to them with the naval victory in. You should have seen them gather round. They threw their hats in the air and started singing and dancing. They didn’t half rejoice over it. No one would have believed goings on round here; it is not a bit like war. We have roaring fires day and night, and it would remind one of a great city lit up by night from a distance.

Leicester Daily Post, 19 February 1915.81

Sergeant E. B. Hayball

C Company, 1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

Christmas Eve found the Battalion trenches covered with snow, and a brilliant moon lit up No Man’s Land and the enemy trenches. After dusk the sniping from the German trenches ceased and the enemy commenced to sing; their Christmas carol grew louder as their numerous troops in the reserve trenches joined in, and eventually ended with loud shouts and cheering. ‘A’ Company of our Battalion then began a good old English carol, the regiments on right and left joining in also, and this was received by the enemy with cheers and shouts of, ‘Good! Good!’

On Christmas Day snow fell heavily, and, as the enemy did not snipe when the men exposed their heads, several of ‘B’ Company got out of their trench and stood upright in full view of the enemy; they were surprised to see the Germans do likewise, waving their hands and shouting in broken English. Orders were given by the Commanding Officer for sentries to be posted on the alert in case the enemy attempted any treachery, and the remainder of the Battalion, quick to take advantage of the opportunity, set to work repairing the trench parapet and collecting wood for fires. At dusk the sentries manned the parapet as usual, but the enemy remained quiet, all except his artillery, who continued to shell the back areas. That night the ration parties were again subjected to the glare of the searchlight on reaching the wood, and, expecting a volley of bullets, the men threw themselves flat, but the enemy infantry did not fire, and after arriving safely back with the rations, etc., the troops gave the Germans a rousing cheer!

Next day rain fell, thaw set in, the trenches collapsed during the day, the enemy recommenced to snipe and shell, Christmas was over and they were back to business. The trenches by this time were in a shocking state in places, owing to the sides falling, being here and there almost as wide as a country lane, with scarce any cover from the enemy snipers.82

Private Stan Brown

1st Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment

On Christmas Eve, as far as we were concerned, we was still at war, but in the evening on sentry-go we heard singing from Jerry.… And our Buchanan-Dunlop who come to us as Battalion Commander, he kind of led the singing!

Interviewed in 1981.83

Appendix 2: successor regiments

With the exception of the Scots Guards, none of the infantry regiments in the account above survives under the name it had during the First World War; some – including The Leicestershire Regiment – have been disbanded. I believe the following list of current regiments which have incorporated those mentioned here, in large part derived from Gerry Murphy, Where Did That Regiment Go? The Lineage of British Infantry and Cavalry Regiments at a Glance, revised edn (Stroud: The History Press, 2016), ISBN: 978 0 7509 6850 8, with some additional information from Wikipedia, is accurate – any errors are my own.

| First World War | Successor regiment |

| Gordon Highlanders (75th) | 4th Battalion The Highlanders (The Royal Regiment of Scotland) |

| Lancashire Fusiliers (20th) | disbanded as 2nd Battalion The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers |

| Leicestershire Regiment (17th) | disbanded as 4th Battalion The Royal Anglian Regiment |

| Middlesex Regiment (57th & 77th) | disbanded as 4th Battalion The Queen’s Regiment |

| North Staffordshire Regiment (64th & 98th) | disbanded as 3rd Battalion The Mercian Regiment |

| Queen’s Westminster Rifles = 16th (County of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (Queen’s Westminsters) | 2nd Battalion The Rifles |

| Rifle Brigade | 4th Battalion The Rifles |

| Royal Berkshire Regiment (49th & 66th) | 1st Battalion The Rifles |

| Royal Scots (1st) | 1st Battalion The Royal Scots Borderers (The Royal Regiment of Scotland) |

| Royal Warwickshire Regiment (6th) | 2nd Battalion The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers |

| West Yorkshire Regiment (14th) | 1st Battalion The Yorkshire Regiment |

Thanks

I have been helped greatly in preparing this piece by Graham and Robin Buchanan-Dunlop, who provided copies of their grandfather’s letters, photographs, and much information; by Kate Henderson, who kindly gave me permission to publish the reproduction of her work; at Loretto, by Gavin McDowall, June C. Dunford, and Jill Smith, who helped provide copies of the Daily Mail and Daily Sketch articles; and by Mike Hill, who generously provided copies and sources of all the accounts of the Leicestershire Regiment’s truce that he had been able to find: thank you all.

Updates

- 24 December 2014: first published.

- 30 December 2014: typos corrected; order of battle adjusted to place Saxons opposite North Staffords on Leicesters’ left, and Westphalians opposite and to right of Leicesters (nn. 16 & 25 adjusted accordingly); Leicesters’ involvement in ceasefires after 27 December clarified; Weintraub reference added to n. 40; ‘young Brown’ identified in new n. 50 [20 February 2015: now n. 53].

- 20 February 2015: typos corrected; references to Wylly’s History of … The Leicestershire Regiment in the Great War added, and additional biographical information/clarification given for Capt Tidswell (in new n. 9), Lt-Col. Croker, Capt. Tollemache, Lt Long/Lang, Capt. Wilson, Lt Herbison, Maj. Stoney Smith, and Lt Brown; Sgt Hayball’s account of the Christmas truce added; images of Battalion HQ, September 1914, and Maj.-Gen. Croker added; occasion of Buchanan-Dunlop’s promotion to CO expanded; notes renumbered accordingly.

- 27 December 2019: Evelyn Williams has written about Archibald and Colin Buchanan-Dunlop, and their connections with Katesgrove in Reading: ‘Katesgrove’s link with carols in the trenches in 1914‘, The Whitley Pump, 24 December 2019.

- 12 January 2022: corrected minor typos. Added: references to Hill, 2014 edition of Seaton & Brown, Buchanan-Dunlop’s Out of the Thorns, and James Morley’s fantastic A Street Near You (which features Colin Buchanan-Dunlop on its home page); Leicesters’ relief of West Yorkshire Regiment; possible identification of Katie; list of other regiments with whom 107th Saxon Regiment held truces; additional examples of comparison between Saxons and Anglo-Saxons; comparison of Buchanan-Dunlop’s account with those of other Leicesters; 2 Scots Guards singing of Good King Wenceslas; appendices 1 and 2.

Notes

- ‘100 years on: remembering the Edinburgh school teacher who stopped the First World War’, Deadline, 6 November 2014, online; ‘Christmas truce hero honoured by school’, Edinburgh Evening News, 7 November 2014, online. See also, for example, ‘The Christmas truce’, Edinburgh and the Lothians Life, November/December 2014, p. 42; ‘Both “sides” to remember First World War Christmas Truce in special service in Musselburgh’, East Lothian Courier, 24 November 2014, online; David Caldwell, ‘Loretto commemorates 1914 Xmas truce with special commission’, Radio Saltire, 2 December 2014, online; Bill Gibb, ‘School’s concert inspired by the day peace broke out at Christmas’, Sunday Post, 7 December 2014, online; ‘100 years on – remembering the Loretto schoolboy who stopped the First World War’, BSA: Boarding Schools Association, 15 December 2014, online. [↩]

- Malcolm Brown and Shirley Seaton, Christmas Truce (London: Leo Cooper in association with Secker and Warburg and New York: Hippocrene Books, 1984), ISBN 0 436 07102 9 / 0 87052 015 6; revised edition (London: Macmillan, 2014), ISBN 978 1 4472 6427 9); see also Stanley Weintraub, Silent Night: The Remarkable Christmas Truce of 1914, paperback ed. (London: Simon & Schuster, 2014), ISBN 978 1 47113 519 4 (first ed. 2001); and Mike Hill, Christmas Truce: By the Men Who Took Part: Letters from the 1914 Ceasefire on the Western Front (n.p.: Fonthill, 2021), ISBN 978 1 78155 812 6. Specific references to Buchanan-Dunlop’s letters in Brown & Seaton, Weintraub, and Hill are given in the notes below. I have not used an initial capital letter when referring to the truce: to do so would give a misleading impression that it was an official event, rather than the disorganised and spontaneous series of occurrences that it seems to have been in reality. [↩]

- Sources for Buchanan-Dunlop’s biography: ‘Buchanan-Dunlop, Archibald Henry – OBE TD’, Have you a Tiger in your family?, online; ‘Buchanan-Dunlop, Archibald Henry’, The Loretto Register, online (membership required); personal communications from Buchanan-Dunlop’s grandson, Graham Buchanan-Dunlop; Robin Buchanan-Dunlop, Out of the Thorns: A Short History of the Buchanan-Dunlops of Drumhead (privately printed, 2019), pp. 142-59. [↩]

- The London Gazette, 25 August 1914, p. 6693. [↩]

- Letter to his wife, 24 November 1914. [↩]

- Until Boxing Day 1916, the battalion was part of the British Expeditionary Force, as part of the 16th Brigade (under Brigadier-General E. C. Ingouville-Williams) holding the line between Rue du Bois and La Grande Flamengrie, in the 6th Division (Major-General Sir John Keir), part of III Corps (Major-General W. P. Pulteney). On 26 December 1914, the BEF was disbanded and III Corps became part of the newly-formed Second Army, commanded by General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien. H. C. Wylly, History of the 1st & 2nd Battalions The Leicestershire Regiment in the Great War (Aldershot: Gale & Polden, s.d.), p. 7; Brown & Seaton 1984, pp. 206-7 & 209; id. 2014, pp. 282 & 286. [↩]

- For whom see, respectively, Buchanan-Dunlop pp. 175-84, 159-65, and 173-5. [↩]

- For Mary, see Buchanan-Dunlop pp. 143-9, 156-7, and 159. [↩]

- In the extracts below, I have retained Buchanan-Dunlop’s orthography: it gives a more vivid picture of his letters than the somewhat tidier versions published by Brown & Seaton. [↩]

- This and subsequent locations are taken from 1 Leicesters’ war diary for the period August 1914-November 1915, The National Archives, WO 95/1611/2; see also Wylly, p. 13. [↩]

- Captain E. S. W. Tidswell. He was wounded sometime between 20 September and the end of the month, and left the Battalion to become Brigade Major to the 81st Brigade in June 1915: Wylly, pp. 8, 16, & 17. [↩]

- Lieutenant-Colonel H. L. Croker, commanding 1st Battalion The Leicestershire Regiment until he took over command of the 81st Brigade on 20 March 1915: Wylly, pp. 8 & 16. [↩]

- Unidentified; I suspect, from a letter of Buchanan-Dunlop’s to Mary on the morning of 13 February 1915, that he may have been a member of staff at Loretto. [↩]

- Published in part in Brown & Seaton 1984, p. 27; id. 2014, p. 29. [↩]

- Emma Turner, née Buchanan-Dunlop, his father’s sister (see Buchanan-Dunlop, p.111); I don’t know what she said. [↩]

- Published in part in Brown & Seaton 1984, p. 20; id. 2014, p. 25. [↩]

- Bac Saint Maur; cf. the note of the event in Wylly, p. 14. [↩]

- His oldest son, Robert Arthur. [↩]

- 1 Leicesters’ war diary, The National Archives, WO 95/1611/2. [↩]

- Infanterie-Regiment Prinz Johann Georg Nr. 107, Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 139 and Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 179, of the 47th and 48th Brigades, 24th Division, XIX (Saxon) Corps; and Infanterie-Regiment Prinz Friedrich der Niederlande (2. Westfälisches) Nr. 15, and Infanterie-Regiment Graf Bülow von Dennewitz (6. Westfälisches) Nr. 55, of the 26th Brigade, 13th Division, VII (Westphalian) Corps. See the German order of battle in Brown & Seaton 1984, p. 211, and the map on p. viii; id. 2014, pp. 288 & xviii. [↩]

- Published in Brown & Seaton 1984, p. 60; id. 2014, p. 64. [↩]

- The carols were listed in an article in the Daily Mail: see below. [↩]

- Published in part in Brown & Seaton 1984, pp. 76 & 114; id. 2014, pp. 83 & 133; Weintraub, p. 150; and Hill, pp. 134-5. [↩]

- ‘Listen: World War One veteran recalls in great detail the famous Christmas truce’, Express, n.d., online. [↩]

- Wylly, p. 15. [↩]

- From a letter of Buchanan-Dunlop’s dated 31 January 1915, this seems to be Captain L. D. S. Tollemache, another company commander in 1 Leicesters. See the list of officers serving in the Battalion on 1 January 1915 in the Leicesters’ war diary, inserted between the entries for 10 and 11 January 1915 (hereafter ‘List of officers’); and Wylly, pp. 8 & 16. [↩]

- Possibly at Grispot. [↩]

- His brother, Colin Napier Buchanan-Dunlop, an officer in the Royal Horse Artillery, serving at the time with the Field Artillery. Colin also materialised in Armentières on 11 February 1915, recorded in a letter from Buchanan-Dunlop to his wife that day: ‘Interrupted by the Colonel who entered with Colin! Such a surprise. He found C riding about looking for this house, & brought him in. So I didn’t go to the Follies but stayed & had tea & a chat with Colin who is looking clean & beautiful as usual, but with the nearest approach to a moustache I’ve yet seen him sporting – about 4 hairs.’ Colin was killed less than a year later, on 14 October 1915, when a shell hit his dugout. See Buchanan-Dunlop, pp. 113-16; and his entry in A Street Near You. [↩]

- His sister, Jean Hamilton Callender; see Buchanan-Dunlop, p. 111. [↩]

- To the Leicesters’ left seems to have been 1st Battalion The North Staffordshire Regiment, opposite the 107th Saxon Regiment (amongst others): Brown & Seaton 1984, p. 155; id. 2014, pp. 184-5. The ‘Prussians’ (also mentioned in Private Hill’s account) are presumably the Westphalians to the Leicesters’ centre and right: see the German order of battle in Brown & Seaton 1984, p. 211, and the map on p. viii; id. 2014 pp. 288 & xviii. [↩]

- Brigadier-General E. C. Ingouville-Williams, commanding 16th Brigade. [↩]

- Published in part in Brown & Seaton 1984, pp. 113 & 114; id. 2014, pp. 133-4; and Weintraub, p. 150. [↩]

- Lieutenant E. C. Long, RAMC: ‘List of officers’; listed in Wylly, pp. 8 & 16, as E. C. Lang. [↩]

- This was Walter C. Wilson, capped in 1907, no. 448 in ‘List of England national rugby union players’, Wikipedia, online. He was wounded in February 1915. ‘List of officers’; Wylly, pp. 8 & 16. [↩]

- Perhaps Buchanan-Dunlop’s niece, Kathleen Voules – the daughter of his sister-in-law Isabel Janet Voules, née Kennedy. [↩]

- Lieutenant C. W. Herbison: ‘List of officers’; Wylly, pp. 16 & 26. [↩]

- Published in part in Brown & Seaton 1984, pp. 163 & 170; id. 2014, pp. 195 & 205; Weintraub, p. 150; and Hill, p. 135. [↩]

- The National Archives, WO 95/1611/2. [↩]

- Brown & Seaton 1984, pp. 155-6; id. 2014, pp. 185-6; Weintraub, pp. 160-61; Hill, pp. 90, 108, 116, & 133. Of the other regiments opposite Buchanan-Dunlop, the 11th (Westphalian) held a truce with 2nd Battalion The Gordon Highlanders and 2nd Battalion The Scots Guards (Hill, pp. 171 & 182); the 139th (Saxon) with 3rd Battalion The Rifle Brigade (Hill, p. 94); and the 179th (Saxon) with 1st Battalion The North Staffordshire Regiment (Hill, p. 129) – the latter amongst the regiments (79th, 102nd, 132nd, and 179th) reportedly still not fighting after six days (Hill, pp. 128-9). [↩]

- Letter to his wife, 3 January 1915. [↩]

- Possibly 1st Battalion The Middlesex Regiment, who relieved 1 Leicesters on 1 January 1915: see the Leicesters’ war diary. [↩]