This April I was in Dublin for a few days, speaking at Collective Imagination 2019, the conference for users of TMS museum collection management software. This is a brief post about the conference and my lecture, and a visit to the Dublin Museum of Natural History.

I find that software user conferences are more useful than they might at first sound: usually organised and funded, at least in part, by the software vendors, they give them an opportunity to meet their clients, and brief them about new developments in, and future plans for, the software. But they also give the users a chance to meet each other face-to-face (there’s usually also an active email list where users regularly provide advice and troubleshoot virtually) – and, crucially, to make their feelings known to the vendors. All of this happened at Collective Imagination this year, and was well worth attending for that alone.

But alongside the conference, Gallery Systems also ran a series of workshops – for those of us based in Europe, a relatively affordable way to pick up some training directly from the system supplier, as it’s normally delivered in New York. I had originally planned to attend one on drawing up report templates for TMS data using Microsoft SQL Server Reporting Services (SSRS), rather than Crystal Reports, the standard system used to date, which has some notable drawbacks – particularly around the handling of images, fairly crucial for a system used in an art gallery like the National Gallery, where I work. Alas, a massively delayed flight meant I missed it.

However, I did get to two other workshops. The first was on thesaurus design and organisation in TMS , which I will find very useful as I convert the Gallery’s flat list of keywords derived from the index to the 2000 CD-ROM of its Complete Illustrated Catalogue into a series of proper, hierarchical thesauruses which can be used to help users browse and filter their way through our collection on our new website, currently being developed. (I’ll be talking about this later this year, at the Collections Trust annual conference at the New Walk Museum and Art Gallery in Leicester on 12 September.)

The second was about drawing up ‘data views’ in TMS. These use XSLT stylesheets to reformat XML representations of the data within the system to produce summaries of information on various screens – it can be quite useful to tweak exactly what users see at a particular point in the system, as it can better reflect the peculiarities of one’s own data, or ways of working. Reassuringly, the amount of XSLT needed for TMS data views seems fairly minimal – it, and particularly the XPath elements of it, are a language I find particularly opaque. This will be helpful over the coming months as my newly-appointed Collection Information Officer will be working to review and reconfigure the exhibitions, loans in, loans out, and other related areas of the Gallery’s copy of TMS so that they better match our procedures, and the system’s capabilities: both have changed significantly since we last carried out this exercise at the Gallery about ten years ago.

After the workshops came the conference proper. Amongst the many papers presented (in multiple strands), the most interesting that I saw were about the online publication of the card index of the Central Depot for Confiscated Collections in Vienna; visualising TMS data using SSRS – and top tips for improving the guidance one writes for one’s TMS users. Of the product previews, the most striking was the new, web-based version of TMS, TMS Collections. As soon as it contains all the modules we currently use, I’ll be considering its installation at the National Gallery very seriously.

I was also flattered to have been asked to give the keynote lecture – particularly because, compared to many of the attendees, I’m a comparative newcomer to TMS, having used and managed the system for just over three years, since starting at the National Gallery. But the Gallery is TMS’s oldest user of the system in the UK: we acquired it in 1999, and went live in 2000. And, of all our systems for managing and publishing collection-related information, TMS, at 20 years and counting, is the longest-lasting.

Kiosks

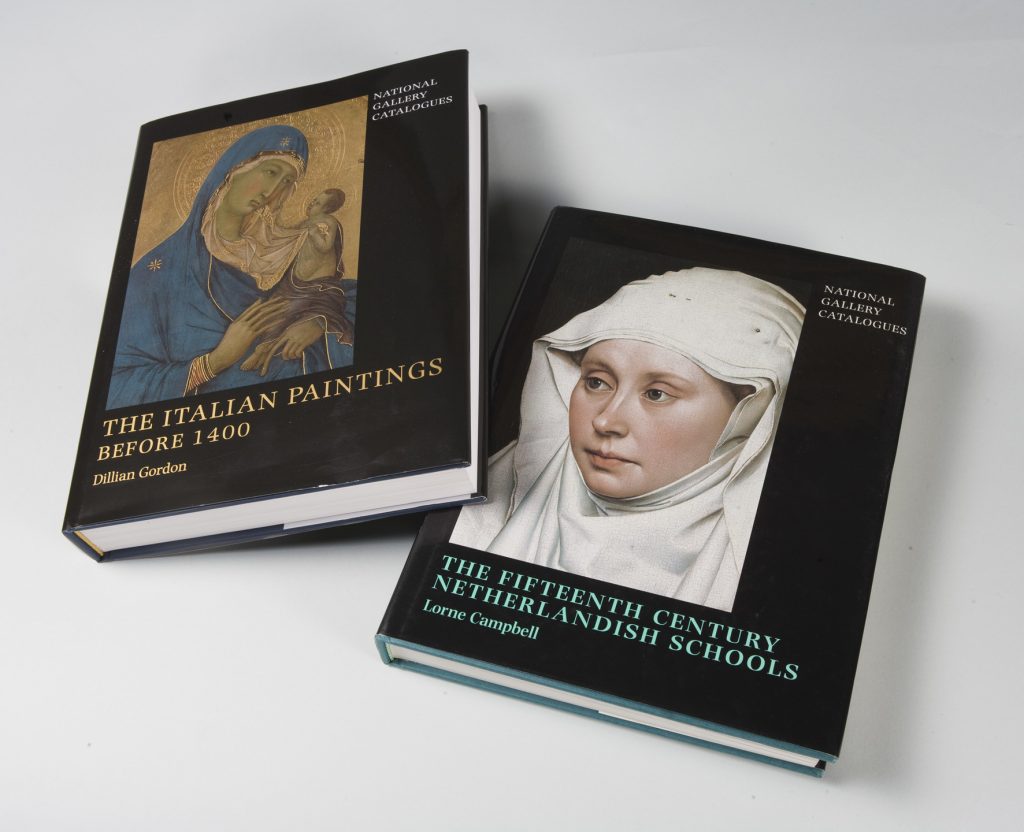

The title of my lecture was ‘From Kiosks to Linked Data: The Digital Cataloguing and Management of the National Gallery’s Collections’. Based initially on the work done when the collection was removed to a slate mine in Wales for safe keeping during the Second World War, the Gallery’s catalogues have had a well-deserved reputation for leading the world in the detail and quality of the research they embody. As our collection is so small, it’s possible to catalogue it in its entirety.

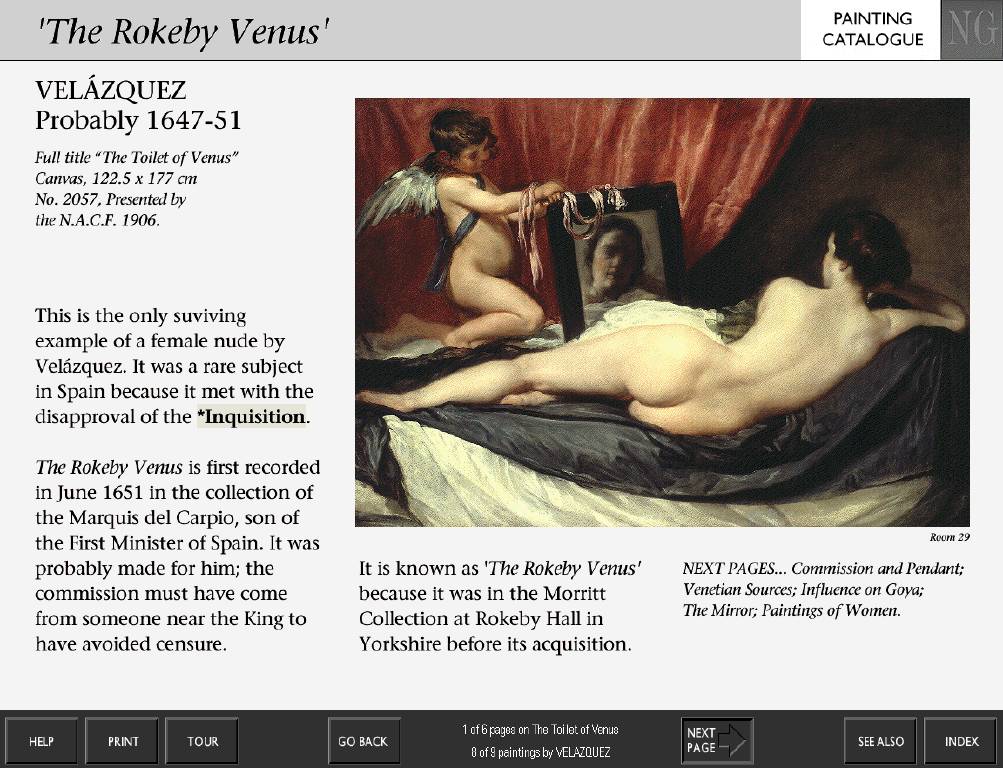

And in 1991, we also led the world in the digital delivery of information about works of art to the public: the opening of the Gallery’s new Sainsbury Wing was used to launch the Micro Gallery, a room full of colour touchscreen terminals developed by Cogapp and using Gallery content, that provided colour or occasionally black-and-white images, and textual descriptions, of all our paintings. Users could find paintings by artist, genre of painting, place and time, or subject matter. Remember, this was when the web was in its infancy: the first web browser was released to the public two months after we launched the Micro Gallery.

The Micro Gallery was a free-standing system: it contained all its own data, rather than draw it from an external source. The same is true of its successor, ArtStart, developed by Nykris Digital Design, which was installed in the Gallery from 2005 until 2014.

In fact, when the Micro Gallery was installed, we had no centralised database of collection information. We eventually installed System Simulation’s Index+ in 1994, before replacing it (for reasons that I still don’t know) with TMS in 1999-2000. But even with TMS, an initial lack of clear ownership and centralised control meant that the data in the system was neither consistent nor reliably up-to-date – and so, basically, unpublishable. It was only thanks to a significant effort by my predecessor as the Gallery’s Collection Information Manager, Gillian Essam, that the data in TMS was made sufficiently reliable to be publishable. From 2009, it delivered the ‘tombstone’ data1 in the collections pages on the Gallery’s website.

With reliable data now in TMS, it was possible to use that data to help manage the Gallery’s collections, and a series of procedures – notably for object movements, loans in, loans out, and exhibitions – were set up in the system by Tim Henbury, during his time working as the Gallery’s Collections Manager from 2005 to 2011. Although his work has served the Gallery well over the intervening years, these are the procedures we’ll be reviewing over the next couple of years: realistically, most museums should aim to have a ongoing rolling programme of procedural reviews every three to five years, as standards such as Spectrum, local ways of working, and collections management systems all evolve.

But what we had never done was use TMS to store catalogue information: only enough to identify and manage the paintings. We seem, fundamentally, to have believed that print was the only authoritative medium in which to store and publish research information. And there’s always a problem taking texts which are fundamentally discursive and nuanced, and trying to fit them into database.

Linked Data

All this has been changing, however. Soon after his appointment in late 2015, the Gallery’s new Director, Gabriele Finaldi, said on national television that:

[T]he Gallery has probably more knowledge about its own collection than any other museum in the world. That’s knowledge that we want to share, it’s knowledge that we want to put out on the internet.2

And so, over the last couple of years, the Gallery’s Collections Information Project has seen us rewrite all the public web texts describing our paintings, as well as digitise all our current published catalogues and try and wrangle existing data for bibliographies out of intractable sources such as Word files. Just as important, though, is the infrastructure that we have set up as part of the project: middleware, in the shape of Knowledge Integration’s CIIM, that enables us to take painting-related information from a series of different datasources –

- Collections management system (TMS)

- Archive management system (Calm)

- Library management system (EOS)

- Collection images database (CID, bespoke-built in SQL Server)

- Non-collection images DAMS (Portfolio)

- Image folders

- Authoring system for the Collections Information Project (DokuWiki)

- Room-booking system (Artifax)

– and link them all together before delivering them as a unified data source via various enpdoints: notably an Elasticsearch index, which will be used to drive our newly-redesigned collections online pages, but also ones designed to be read by machines – an OAI-PMH server; and Linked Data, served as both individual pages of RDF data, and a SPARQL endpoint. This should make it much easier for us to collaborate with digital projects – and for me to fulfil my ambition of never having to fill in someone else’s spreadsheet with data about the Gallery’s objects ever again.

The Dead Zoo

I’d originally planned to spend the evening I arrived having a drink with a former colleague from my time at the Horniman Museum, Paolo Viscardi – but the delay to my flight put paid to that. So I arranged to meet Paolo for coffee the day after the conference, when my wife had joined me to do a little sightseeing before we flew back to the UK. (For those of you who, like us, find a old library irresistible: Marsh’s Library is highly recommended.) Paolo is now an Assistant Keeper at the Natural History Museum in Dublin, one branch of the National Museum of Ireland, where he’s responsible for the zoology and entomology collections.

Paolo being Paolo, a quick cup of coffee meant that Julia and I left three hours later, having been taken round pretty much everything there was to see. The museum itself is striking: it’s popularly known as the Dead Zoo, and it’s easy to see why when one looks at the galleries of taxidermied specimens.

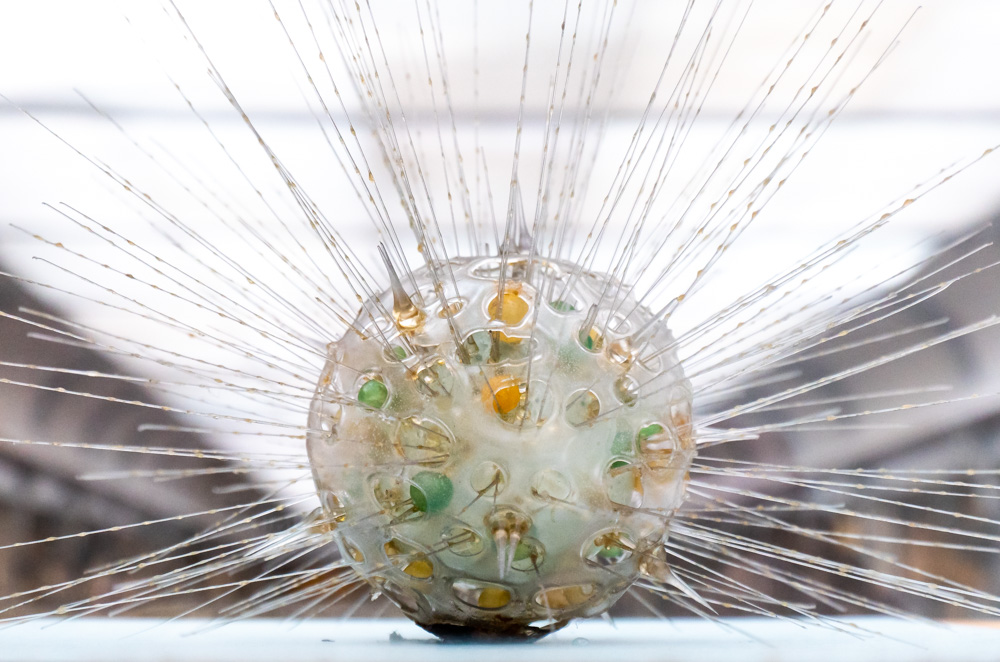

But one of the major attractions is not currently on public show: the Museum’s Blasckha glass models of marine creatures. These were created by the Dresden firm of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, and based on the latest scientific publications – Paolo showed us examples where the literature had misunderstood the organism’s nature, and these misunderstandings were then incorporated into the firm’s models.

The models were then shipped to museums and collectors around the world. This, in itself, is a minor miracle: I first knowingly saw a Blaschka model – of a radiolarian – at the Curiosity exhibition at Turner Contemporary (whence the Horniman Walrus had gone for a summer outing), and immediately thought: how on earth could that have been packed and transported?

Paolo also told us about the project he is involved with, alongside Emmanuel Reynaud of University College, Dublin, to collate known Blaschka specimens worldwide with the firm’s published catalogues – and their current scientific names, the majority of which are different from the names under which the models were acquired. You can follow their work on Twitter, via the #BlaschkaMonday hashtag.3

This will be a significant help to collections for many reasons. Obviously, it will given them a better idea of what they own, and, by identifying the species, enable them to make better use of their collection as a tool for education and engagement. But it will also help owners care for their collections: the materials used by the Blachkas changed as their skill increased and they became busier, so knowing what precisely what you have – or being able to collate a species name or acquisition date with a production date from the catalogue – means that conservators will have a much better idea of what they might encounter when working with a model. It was good to end a visit to Dublin that had started with nitty-gritty discussions of the technical aspects of museum documentation with another reminder (if one were needed) of how it can help us care for museum collections and present them to the world.

Updates

28 June 2019: tags added, caption of Blaschka model Radiolarian updated with object details (with thanks to Paolo Viscardi)

Notes

- The basic facts about an object that identify it – so-called because they might appear on an object’s tombstone, if it had one. [↩]

- Newsnight , BBC2, 4 January 2016 [↩]

- And see the preprint Eric Callaghan, Bernhard Egger, Hazel Doyle, Emmanuel G. Reynaud, ‘Taxonomic revision of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka Glass Models of Invertebrates 1888 Catalogue, with correction of authorities’, bioRxiv 408260; doi:10.1101/408260 [↩]